Portal:History of science

The History of Science Portal

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

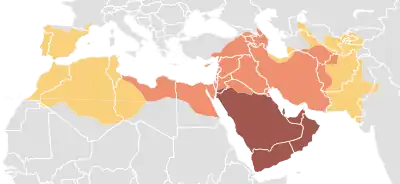

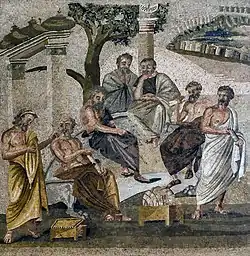

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3000 to 1200 BCE. These civilizations' contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced later Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages, but continued to thrive in the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman (or Byzantine) Empire. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the Hellenistic worldview was preserved and absorbed into the Arabic-speaking Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West.

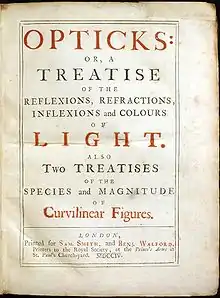

Natural philosophy was transformed during the Scientific Revolution in 16th- to 17th-century Europe, as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The New Science that emerged was more mechanistic in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined scientific method. More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The chemical revolution of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for chemistry. In the 19th century, new perspectives regarding the conservation of energy, age of Earth, and evolution came into focus. And in the 20th century, new discoveries in genetics and physics laid the foundations for new subdisciplines such as molecular biology and particle physics. Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science," particularly after the Second World War. (Full article...)

Selected article -

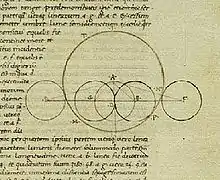

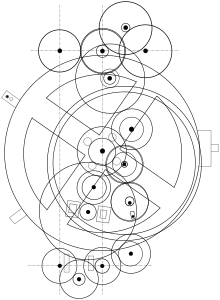

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed stars and planets are accounted for by treating them as embedded in rotating spheres made of an aetherial, transparent fifth element (quintessence), like jewels set in orbs. Since it was believed that the fixed stars did not change their positions relative to one another, it was argued that they must be on the surface of a single starry sphere.

In modern thought, the orbits of the planets are viewed as the paths of those planets through mostly empty space. Ancient and medieval thinkers, however, considered the celestial orbs to be thick spheres of rarefied matter nested one within the other, each one in complete contact with the sphere above it and the sphere below. When scholars applied Ptolemy's epicycles, they presumed that each planetary sphere was exactly thick enough to accommodate them. By combining this nested sphere model with astronomical observations, scholars calculated what became generally accepted values at the time for the distances to the Sun: about 4 million miles (6.4 million kilometres), to the other planets, and to the edge of the universe: about 73 million miles (117 million kilometres). The nested sphere model's distances to the Sun and planets differ significantly from modern measurements of the distances, and the size of the universe is now known to be inconceivably large and continuously expanding. (Full article...)Selected image

_(1827%E2%80%931830).jpg.webp)

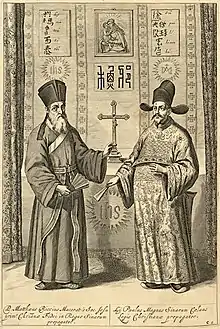

1675 image of a Chinese astronomer with an elaborate armillary sphere. In the 17th century, Chinese astronomers collaborated extensively with Jesuit scholars, who brought the Copernican and Tychonic systems from Europe.

Did you know

...that Einstein's famous letter to FDR about the possibility of an atomic bomb was actually written by Leó Szilárd?

...that geology was transformed in the latter part of the 20th century after widespread acceptance of plate tectonics?

...that the idea of biological evolution dates to the ancient world?

Selected Biography -

Turing c. 1928 |

Alan Mathison Turing OBE FRS (/ˈtjʊərɪŋ/; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer science, providing a formalisation of the concepts of algorithm and computation with the Turing machine, which can be considered a model of a general-purpose computer. He is widely considered to be the father of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence.

Born in Maida Vale, London, Turing was raised in southern England. He graduated at King's College, Cambridge, with a degree in mathematics. Whilst he was a fellow at Cambridge, he published a proof demonstrating that some purely mathematical yes–no questions can never be answered by computation and defined a Turing machine, and went on to prove that the halting problem for Turing machines is undecidable. In 1938, he obtained his PhD from the Department of Mathematics at Princeton University. During the Second World War, Turing worked for the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park, Britain's codebreaking centre that produced Ultra intelligence. For a time he led Hut 8, the section that was responsible for German naval cryptanalysis. Here, he devised a number of techniques for speeding the breaking of German ciphers, including improvements to the pre-war Polish bomba method, an electromechanical machine that could find settings for the Enigma machine. Turing played a crucial role in cracking intercepted coded messages that enabled the Allies to defeat the Axis powers in many crucial engagements, including the Battle of the Atlantic. (Full article...)Selected anniversaries

April 9:

- 1770 - Birth of Thomas Johann Seebeck, German physicist (d. 1831)

- 1889 - Death of Michel Eugène Chevreul, French chemist (b. 1786)

- 1928 - Birth of Tom Lehrer, American musician and mathematician

- 1930 - Birth of F. Albert Cotton, American chemist (d. 2007)

- 1932 - Birth of Jim Fowler, American zoologist

- 1951 - Death of Vilhelm Bjerknes, Norwegian physicist (b. 1862)

- 1953 - Warner Brothers premieres the first 3-D film, entitled House of Wax

- 1957 - The Suez Canal in Egypt is cleared and opens to shipping

- 2002 - Death of Leopold Vietoris, Austrian mathematician (b. 1891)

Related portals

Topics

General images

Subcategories

Things you can do

Help out by participating in the History of Science Wikiproject (which also coordinates the histories of medicine, technology and philosophy of science) or join the discussion.

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus

-

List of all portalsList of all portals

List of all portalsList of all portals -

The arts portal

The arts portal -

Biography portal

Biography portal -

Current events portal

Current events portal -

Geography portal

Geography portal -

History portal

History portal -

Mathematics portal

Mathematics portal -

Science portal

Science portal -

Society portal

Society portal -

Technology portal

Technology portal -

Random portalRandom portal

Random portalRandom portal -

WikiProject PortalsWikiProject Portals

WikiProject PortalsWikiProject Portals

_Venenbild.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)