Polychrome

Polychrome is the "practice of decorating architectural elements, sculpture, etc., in a variety of colors."[1] The term is used to refer to certain styles of architecture, pottery or sculpture in multiple colors.

When looking at artworks and architecture from antiquity and the middle ages, people tend to believe that they were monochrome. In reality, the pre-Renaissance past was full of colour, and all the Greco-Roman sculptures and Gothic cathedrals, that are now white, beige or grey, were initially painted in bright colours. As André Malraux stated, "Athens was never white but her statues, bereft of color, have conditioned the artistic sensibilities of Europe... the whole past has reached us colorless."[2] Polychrome was and is a practice not limited only to the Western world. Non-Western artworks, like Chinese temples, Oceanian Uli figures, or Maya ceramic vases, were also decorated with colours.

Ancient Near East

Tile with a guilloche border from the North-West Palace at Nimrud (now in modern Iraq), 883-859 BC, glazed earthenware, British Museum, London[4]

Tile with a guilloche border from the North-West Palace at Nimrud (now in modern Iraq), 883-859 BC, glazed earthenware, British Museum, London[4]

.jpg.webp) Reconstruction of a hall from an Assyrian palace, by Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1849

Reconstruction of a hall from an Assyrian palace, by Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1849

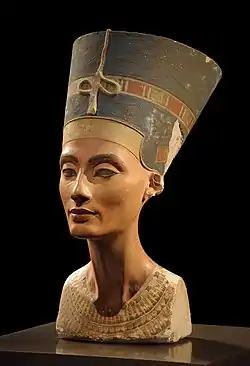

Ancient Egypt

Thanks to the dry climate of Egypt, the original colours of many ancient sculptures in round, reliefs, paintings and various objects were well preserved. Some of the best preserved examples of ancient Egyptian architecture were the tombs, covered inside with sculpted reliefs painted in bright colours or just frescos. Egyptian artists primarily worked in black, red, yellow, brown, blue, and green pigments. These colours were derived from ground minerals, synthetic materials (Egyptian blue, Egyptian green, and frits used to make glass and ceramic glazes), and carbon-based blacks (soot and charcoal). Most of the minerals were available from local supplies, like iron-oxide pigments (red ochre, yellow ochre, and umber); white derived from the calcium carbonate found in Egypt's extensive limestone hills; and blue and green from azurite and malachite.

Besides their decorative effect, colours were also used for their symbolic associations. Colours on sculptures, coffins, and architecture had both aesthetic and symbolic qualities. Ancient Egyptians saw black as the colour of the fertile alluvial soil, and so associated it with fertility and regeneration. Black was also associated with the afterlife, and was the colour of funerary deities like Anubis. White was the colour of purity, while green and blue were associated with vegetation and rejuvenation. Because of this, Osiris was often shown with green skin, and the faces of coffins from the 26th Dynasty were often green. Red, orange, and yellow were associated with the sun. Red was also the colour of the deserts, and hence associated with Seth and the forces of destruction.[6][7]

Colossal statue of Tutankhamun, c.1355-1315 BC, painted quartzite, Grand Egyptian Museum, Giza, Egypt

Colossal statue of Tutankhamun, c.1355-1315 BC, painted quartzite, Grand Egyptian Museum, Giza, Egypt

Composite papyrus capital, c.380–343 BC, polychrome sandstone, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Composite papyrus capital, c.380–343 BC, polychrome sandstone, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City Winged sun on a cavetto at the Medinet Habu temple complex, Egypt, unknown architect, unknown date

Winged sun on a cavetto at the Medinet Habu temple complex, Egypt, unknown architect, unknown date

Classical world

Some very early polychrome pottery has been excavated on Minoan Crete such as at the Bronze Age site of Phaistos.[8] In ancient Greece sculptures were painted in strong colors. The paint was frequently limited to parts depicting clothing, hair, and so on, with the skin left in the natural color of the stone. But it could cover sculptures in their totality. The painting of Greek sculpture should not merely be seen as an enhancement of their sculpted form but has the characteristics of a distinct style of art. For example, the pedimental sculptures from the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina have recently been demonstrated to have been painted with bold and elaborate patterns, depicting, amongst other details, patterned clothing. The polychrome of stone statues was paralleled by the use of materials to distinguish skin, clothing and other details in chryselephantine sculptures, and by the use of metals to depict lips, nipples, etc., on high-quality bronzes like the Riace bronzes.

An early example of polychrome decoration was found in the Parthenon atop the Acropolis of Athens. By the time European antiquarianism took off in the 18th century, however, the paint that had been on classical buildings had completely weathered off. Thus, the antiquarians' and architects' first impressions of these ruins were that classical beauty was expressed only through shape and composition, lacking in robust colors, and it was that impression which informed neoclassical architecture. However, some classicists such as Jacques Ignace Hittorff noticed traces of paint on classical architecture and this slowly came to be accepted. Such acceptance was later accelerated by observation of minute color traces by microscopic and other means, enabling less tentative reconstructions than Hittorff and his contemporaries had been able to produce. An example of classical Greek architectural polychrome may be seen in the full size replica of the Parthenon exhibited in Nashville, Tennessee, US.

Traces of paint depicting embroidered patterns on the peplos of an Archaic kore, c.530 BC, marble, Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece

Traces of paint depicting embroidered patterns on the peplos of an Archaic kore, c.530 BC, marble, Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece Polychrome on the Peplos Kore, c.530 BC, Parian marble, Acropolis Museum

Polychrome on the Peplos Kore, c.530 BC, Parian marble, Acropolis Museum Peplos Kore color reconstruction

Peplos Kore color reconstruction Reconstructed color scheme on a Trojan archer from the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina

Reconstructed color scheme on a Trojan archer from the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina.jpg.webp)

Greek statue of a woman with blue and gilt garment from Tanagra, 325–300 BC, gilt and painted terracotta, Antikensammlung Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Greek statue of a woman with blue and gilt garment from Tanagra, 325–300 BC, gilt and painted terracotta, Antikensammlung Berlin, Berlin, Germany Ancient Greek woman head from Taranto, end of the 4th century BC, terracotta, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig, Basel, Switzerland

Ancient Greek woman head from Taranto, end of the 4th century BC, terracotta, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig, Basel, Switzerland Reconstruction of the original polychromy of a Roman portrait of emperor Caligula

Reconstruction of the original polychromy of a Roman portrait of emperor Caligula Greek figurine of a beautifully dressed young woman, 3rd of 2nd century BC, terracotta with kaolin and traces of polychromy, Liebieghaus, Frankfurt, Germany[10]

Greek figurine of a beautifully dressed young woman, 3rd of 2nd century BC, terracotta with kaolin and traces of polychromy, Liebieghaus, Frankfurt, Germany[10].webp.png.webp) Reconstruction of the Temple of Empedocles at Selinunte, Sicily, by Jacques Ignace Hittorff, 1830 (published in 1851)[11]

Reconstruction of the Temple of Empedocles at Selinunte, Sicily, by Jacques Ignace Hittorff, 1830 (published in 1851)[11] Ornaments of the Temple of Empedocles at Selinunte, by Jacques Ignace Hittorff, 1846 (published in 1851)

Ornaments of the Temple of Empedocles at Selinunte, by Jacques Ignace Hittorff, 1846 (published in 1851)%252C_reconstructed_elevation_of_the_main_facade_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Reconstructed elevation of the main facade of the Temple T at Selinunte, Sicily, by Jacques Ignace Hittorff, before 1859

Reconstructed elevation of the main facade of the Temple T at Selinunte, Sicily, by Jacques Ignace Hittorff, before 1859

Medieval world

Throughout medieval Europe religious sculptures in wood and other media were often brightly painted or colored, as were the interiors of church buildings. These were often destroyed or whitewashed during iconoclast phases of the Protestant Reformation or in other unrest such as the French Revolution, though some have survived in museums such as the V&A, Musée de Cluny and Louvre. The exteriors of churches were painted as well, but little has survived. Exposure to the elements and changing tastes and religious approval over time acted against their preservation. The "Majesty Portal" of the Collegiate church of Toro is the most extensive remaining example, due to the construction of a chapel which enclosed and protected it from the elements just a century after it was completed.[12]

_-_Tympan_du_Porche.jpg.webp) Last Judgement tympanum, Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy, Conques, France, early 12th century

Last Judgement tympanum, Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy, Conques, France, early 12th century Statues of Charles V and Joanna of Bourbon, probably from the east facade of the Louvre Castle, 14th century, stone with traces of polychrome[13]

Statues of Charles V and Joanna of Bourbon, probably from the east facade of the Louvre Castle, 14th century, stone with traces of polychrome[13]

Portal at the Collegiate Church of Toro

Portal at the Collegiate Church of Toro.jpg.webp) Bust of the Virgin, c.1390-1395, terracotta with paint, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Bust of the Virgin, c.1390-1395, terracotta with paint, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City Irene, daughter of Cratin, painting a sculpture of the Virgin Mary, France, 1401-1402. Detail from Giovanni Bocaccio's De Claris mulieribus (Concerning famous women), 1403 edition, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Irene, daughter of Cratin, painting a sculpture of the Virgin Mary, France, 1401-1402. Detail from Giovanni Bocaccio's De Claris mulieribus (Concerning famous women), 1403 edition, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris Crib of the infant Jesus, 15th century, wood, lead, silver-gilt, painted parchment, silk embroidery with seed pearls, gold thread, translucent enamels, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Crib of the infant Jesus, 15th century, wood, lead, silver-gilt, painted parchment, silk embroidery with seed pearls, gold thread, translucent enamels, Metropolitan Museum of Art Baptism of Christ, by Veit Stoss, c.1480–1490, limewood with paint and gilding, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Baptism of Christ, by Veit Stoss, c.1480–1490, limewood with paint and gilding, Metropolitan Museum of Art Saint Barbara, c.1490, limewood with paint, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Saint Barbara, c.1490, limewood with paint, Metropolitan Museum of Art Enthroned Virgin, c. 1490-1500, limewood with gesso, paint and gilding, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Enthroned Virgin, c. 1490-1500, limewood with gesso, paint and gilding, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Baroque and Rococo periods

While stone and metal sculpture normally remained uncolored, like the classical survivals, polychromed wood sculptures were produced by Spanish artists: Juan Martínez Montañés, Gregorio Fernández (17th century); German: Ignaz Günther, Philipp Jakob Straub (18th century), or Brazilian: Aleijadinho (19th century).

With the arrival of European porcelain in the 18th century, brightly colored pottery figurines with a wide range of colors became very popular.

Monochromatic color solutions of architectural orders were also designed in the late, dynamic Baroque, drawing on the ideas of Borromini and Guarini. Single-colored stone cladding was used: light sandstone, as in the case of the façade of the Bamberg Jesuit church (Gunzelmann 2016) designed by Georg and Leonhard Dientzenhofer (1686–1693), the façade of the monastery church in Michelsberg by Leonard Dientzenhofer (1696), and the abbey church in Neresheim by J.B. Neumann (1747–1792).[14]

Baroque - Church of San Francisco Acatepec, San Andrés Cholula, Mexico, unknown artchitect, 17th–18th centuries

Baroque - Church of San Francisco Acatepec, San Andrés Cholula, Mexico, unknown artchitect, 17th–18th centuries.jpg.webp) Baroque - The Entombment of Christ, by Luisa Roldán, 1700-1701, polychrome terracotta, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Baroque - The Entombment of Christ, by Luisa Roldán, 1700-1701, polychrome terracotta, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City Rococo - Apartment of Madame du Barry, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France, by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, 18th century

Rococo - Apartment of Madame du Barry, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France, by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, 18th century Rococo - Pilgrimage Church of Wies, Steingaden, Germany, by Dominikus and Johann Baptist Zimmermann, 1754[16]

Rococo - Pilgrimage Church of Wies, Steingaden, Germany, by Dominikus and Johann Baptist Zimmermann, 1754[16]_MET_DP-13079-009.jpg.webp) Rococo - elephant-head vase (vase à tête d'éléphant), by the Sèvres porcelain factory, c.1756-1762, soft-paste porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rococo - elephant-head vase (vase à tête d'éléphant), by the Sèvres porcelain factory, c.1756-1762, soft-paste porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art_(one_of_a_pair)_MET_DP155339.jpg.webp) Rococo - wall sconce (bras de cheminée), by the Sèvres porcelain factory, c.1761, soft-paste porcelain and gilt bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rococo - wall sconce (bras de cheminée), by the Sèvres porcelain factory, c.1761, soft-paste porcelain and gilt bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art_MET_DP-12374-049.jpg.webp) Rococo - perfume vase, by the Chelsea porcelain factory, c.1761, soft-paste porcelain and burnished gold ground, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rococo - perfume vase, by the Chelsea porcelain factory, c.1761, soft-paste porcelain and burnished gold ground, Metropolitan Museum of Art Chinoiserie - Chinese Pavilion (Ekerö Municipality, Sweden), 1763–1769, by Carl Fredrik Adelcrantz[17]

Chinoiserie - Chinese Pavilion (Ekerö Municipality, Sweden), 1763–1769, by Carl Fredrik Adelcrantz[17].jpg.webp) Rococo - The Music Lesson, by the Chelsea porcelain factory, c.1765, soft-paste porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rococo - The Music Lesson, by the Chelsea porcelain factory, c.1765, soft-paste porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art Louis XVI style - vase, 2nd half of the 18th century, porcelain, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Louis XVI style - vase, 2nd half of the 18th century, porcelain, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam_MET_ES6929.jpg.webp) Neoclassical - armchair, c.1780, carved and polychromed walnut, received upholstered in beige silk brocade, currently upholstered with modern cotton and linen velvet, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Neoclassical - armchair, c.1780, carved and polychromed walnut, received upholstered in beige silk brocade, currently upholstered with modern cotton and linen velvet, Metropolitan Museum of Art

19th century

Despite evidence of polychrome being discovered on Ancient Greek architecture and sculptures, most Neoclassical buildings have white or beige facades, and black metalwork. Around 1840, the French architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff, published studies of Sicilian architecture, documenting extensive evidence of color. The 'polychrome controversy' raged for over a decade and proved to be a challenge for Neoclassical architects throughout Europe.[11]

Polychrome brickwork is a style of architectural brickwork which emerged in the 1860s and used bricks of different colors (typically brown, cream and red) in patterned combination to highlight architectural features. It was often used to replicate the effect of quoining and to decorate around windows. Early examples featured banding, with later examples exhibiting complex diagonal, criss-cross, and step patterns, in some cases even writing using bricks.

Polychromatic façade of the Cirque Nationale, Paris, by Jakob Ignaz Hittorff, 1840[18]

Polychromatic façade of the Cirque Nationale, Paris, by Jakob Ignaz Hittorff, 1840[18].jpg.webp) Interior of the St Giles' Catholic Church, Cheadle, Staffordshire, the UK, by Augustus Pugin, 1840-1846[19]

Interior of the St Giles' Catholic Church, Cheadle, Staffordshire, the UK, by Augustus Pugin, 1840-1846[19]

.jpg.webp) Sculpted decoration on the ceiling of the Salon des Sept cheminées, Louvre Palace, Paris, by Francisque Duret, 1851[21]

Sculpted decoration on the ceiling of the Salon des Sept cheminées, Louvre Palace, Paris, by Francisque Duret, 1851[21] Sculpted decoration on the ceiling of the Salon Carré, Louvre Palace, by Pierre-Charles Simart, 1851[22]

Sculpted decoration on the ceiling of the Salon Carré, Louvre Palace, by Pierre-Charles Simart, 1851[22] Chimney-piece in the Chaucer Room of the Cardiff Castle, Cardiff, the UK, by William Burges, c.1877-1890[23]

Chimney-piece in the Chaucer Room of the Cardiff Castle, Cardiff, the UK, by William Burges, c.1877-1890[23]

.jpg.webp)

Rippon Lea Estate, in Australia has polychrome brickwork patterns

Rippon Lea Estate, in Australia has polychrome brickwork patterns

20th century

In the twentieth century there were notable periods of polychromy in architecture, from the expressions of Art Nouveau throughout Europe, to the international flourishing of Art Deco or Art Moderne, to the development of postmodernism in the latter decades of the century. During these periods, brickwork, stone, tile, stucco and metal facades were designed with a focus on the use of new colors and patterns, while architects often looked for inspiration to historical examples ranging from Islamic tilework to English Victorian brick. In the 1970s and 1980s, especially, architects working with bold colors included Robert Venturi (Allen Memorial Art Museum addition; Best Company Warehouse), Michael Graves (Snyderman House; Humana Building), and James Stirling (Neue Staatsgalerie; Arthur M. Sackler Museum), among others.

Panel of polychrome bricks on the exterior of the Vakantiehuis De Vonk, a house in Noordwijkerhout, the Netherlands, by Theo van Doesburg, 1917-1919[26]

Panel of polychrome bricks on the exterior of the Vakantiehuis De Vonk, a house in Noordwijkerhout, the Netherlands, by Theo van Doesburg, 1917-1919[26].jpg.webp)

United States

Polychrome building facades later rose in popularity as a way of highlighting certain trim features in Victorian and Queen Anne architecture in the United States. The rise of the modern paint industry following the American Civil War also helped to fuel the (sometimes extravagant) use of multiple colors.

.JPG.webp)

The polychrome facade style faded with the rise of the 20th century's revival movements, which stressed classical colors applied in restrained fashion and, more importantly, with the birth of modernism, which advocated clean, unornamented facades rendered in white stucco or paint. Polychromy reappeared with the flourishing of the preservation movement and its embrace of (what had previously been seen as) the excesses of the Victorian era and in San Francisco, California in the 1970s to describe its abundant late-nineteenth-century houses. These earned the endearment 'Painted Ladies', a term that in modern times is considered kitsch when it is applied to describe all Victorian houses that have been painted with period colors.

John Joseph Earley (1881–1945) developed a "polychrome" process of concrete slab construction and ornamentation that was admired across America. In the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area, his products graced a variety of buildings — all formed by the staff of the Earley Studio in Rosslyn, Virginia. Earley's Polychrome Historic District houses in Silver Spring, Maryland were built in the mid-1930s. The concrete panels were pre-cast with colorful stones and shipped to the lot for on-site assembly. Earley wanted to develop a higher standard of affordable housing after the Depression, but only a handful of the houses were built before he died; written records of his concrete casting techniques were destroyed in a fire. Less well-known, but just as impressive, is the Dr. Fealy Polychrome House that Earley built atop a hill in Southeast Washington, D.C. overlooking the city. His uniquely designed polychrome houses were outstanding among prefabricated houses in the country, appreciated for their Art Deco ornament and superb craftsmanship.

Native American ceramic artists, in particular those in the Southwest, produced polychrome pottery from the time of the Mogollon cultures and Mimbres peoples to contemporary times.[28]

Polychromatic light

The term polychromatic means having several colors. It is used to describe light that exhibits more than one color, which also means that it contains radiation of more than one wavelength. The study of polychromatics is particularly useful in the production of diffraction gratings.

See also

- Encarnación Spanish form of polychrome sculpture

- Gods in Color (exhibition)

- Monochrome (opposite of polychrome)

Notes

- Harris, Cyril M., ed. Illustrated Dictionary of Historic Architecture, Dover Publications, New York, c. 1977, 1983 edition

- Vinzenz Brinkmann, Renée Dreyfus, Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, John Camp, Heinrich Piening, Oliver Primavesi (2017). GODS IN COLOR Polychromy in the Ancient World. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and DelMonico Books. p. 65. ISBN 978-3-7913-5707-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - van Lemmen, Hans (2013). 5000 Years of Tiles. The British Museum Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7141-5099-4.

- van Lemmen, Hans (2013). 5000 Years of Tiles. The British Museum Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7141-5099-4.

- Fortenberry 2017, p. 6.

- Vinzenz Brinkmann, Renée Dreyfus, Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, John Camp, Heinrich Piening, Oliver Primavesi (2017). GODS IN COLOR Polychromy in the Ancient World. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and DelMonico Books. p. 62 & 63. ISBN 978-3-7913-5707-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wilkinson, Toby (2008). Dictionary of ANCIENT EGYPT. Thames and Hudson. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-500-20396-5.

- C. Michael Hogan, Knossos Fieldnotes, The Modern Antiquarian (2007)

- Jones 2014, p. 37.

- Vinzenz Brinkmann, Renée Dreyfus, Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, John Camp, Heinrich Piening, Oliver Primavesi (2017). GODS IN COLOR Polychromy in the Ancient World. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and DelMonico Books. p. 144. ISBN 978-3-7913-5707-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bergdoll 2000, pp. 176.

- Katz, Melissa R. Architectural Polychromy and the Painters' Trade in Medieval Spain. Gesta. Vol. 41, No. 1, Artistic Identity in the Late Middle Ages (2002), pp. 3–14

- Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- Ludwig, Bogna. 2022. The Polychrome in Expression of Baroque Façade Architecture. Arts 11: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts 11060113

- Martin, Henry (1927). Le Style Louis XIV (in French). Flammarion. p. 31.

- Jones 2014, p. 238.

- "Kina slott, Drottningholm". www.sfv.se. National Property Board of Sweden. Archived from the original on August 6, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 443. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 503. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- Jones 2014, p. 286.

- Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. p. 122. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. p. 122. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 509. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 509. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- Mariana Celac, Octavian Carabela and Marius Marcu-Lapadat (2017). Bucharest Architecture - an annotated guide. Ordinul Arhitecților din România. p. 90. ISBN 978-973-0-23884-6.

- van Lemmen, Hans (2013). 5000 Years of Tiles. The British Museum Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-7141-5099-4.

- van Lemmen, Hans (2013). 5000 Years of Tiles. The British Museum Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-7141-5099-4.

- Center for New Mexico Archaeology. "The Classification System". Office of Archaeological Studies, Pottery Typology Project. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

References

- Bergdoll, Barry (2000). European Architecture 1750-1890. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284222-0.

- Fortenberry, Diane (2017). The Art Museum (Revised ed.). London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-7502-6. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- Rogers, Richard; Gumuchdjian, Philip; Jones, Denna (2014). Architecture The Whole Story. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-29148-1.

External links

Media related to Polychromy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Polychromy at Wikimedia Commons- Research in the field of ancient polychrome sculpture In German

- Amiens Cathedral in Colour

- Polychromatic, Reference.com's definition.