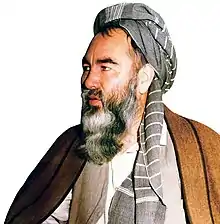

Abdul Ali Mazari

Abdul Ali Mazari (Persian: عبدالعلی مزاری; 1946 – March 13, 1995) [1] was an ethnic Hazara politician, leader of the Hezbe Wahdat party during and following the Soviet–Afghan War,[2][3] who believed that the solution to the internal divisions in Afghanistan was in a federal system of governance, with each ethnic group having specific constitutional rights and able to govern their land and people.[4] He was captured during negotiations and killed by the Taliban in 1995,[5] and posthumously given the title ‘Martyr Of National Unity’ in 2016 by Ashraf Ghani government.[6][7] He supported equal representation of all ethnic groups of Afghanistan, especially Hazaras, who claim that they are being persecuted by other political groups.[8][9][10]

Abdul Ali Mazari استاد عبدالعلی مزاری | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader of Hezbe Wahdat | |

| In office 1989 – 13 March 1995 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1946 Charkent, Balkh province, Afghanistan |

| Died | 13 March 1995 (aged 48–49) Ghazni city, Ghazni province, Afghanistan |

| Political party | Hezbe Wahdat |

| Occupation | Mujahideen commander; politician |

| Awards | Mim Hea Mim peace award |

| Ethnicity | Hazara |

| Nickname | Baba Mazari (Dari: بابه مزاری) |

Early life

Abdul Ali Mazari was born in the Charkent district of Balkh province, south of the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif. He began his primary schooling in theology at the local school in his hometown, then went to Mazar-i-Sharif and later to Qom, Iran and to Najaf, Iraq.

Mujahideen commander and politician

During the Soviet–Afghan War, Mazari returned to Afghanistan and gained a prominent place in the mujahideen resistance movement. During the first years of the resistance, he lost his young brother, Mohammed Sultan, during a battle against the Soviet-backed forces. He soon lost his sister and other members of his family in the resistance. His uncle, Mohammad Ja'afar, and his son, Mohammad Afzal, were imprisoned and killed by the Soviet-backed Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. His father, Haji Khudadad, and his brother, Haji Mohammad Nabi, were killed as well in the war.

Abdul Ali Mazari was one of the founding members and the first leader of the Hezbe Wahdat ("Unity Party"). In the first party congress in Bamiyan, he was elected leader of the Central Committee and in the second congress, he was elected Secretary General. Mazari's initiative led to the creation of the Jonbesh-e Shamal or (Northern Movement), in which the country's most significant military forces joined ranks with the rebels, leading to a coup d'état and the eventual downfall of the Communist regime in Kabul.

After the 1992 fall of Kabul, the Afghan political parties agreed on a peace and power-sharing agreement, the Peshawar Accords, which created the Islamic State of Afghanistan and appointed an interim government for a transitional period to be followed by general elections. According to Human Rights Watch:

The sovereignty of Afghanistan was vested formally in the Islamic State of Afghanistan, an entity created in April 1992, after the fall of the Soviet-backed Najibullah government. ... With the exception of Pashtun warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, all of the parties... were ostensibly unified under this government in April 1992. ... Hekmatyar's Hezbe Islami, for its part, refused to recognize the government for most of the period discussed in this report and launched attacks against government forces but the shells and rockets fell everywhere in Kabul resulting in many civilian casualties.[11]

The Hezbe Wahdat initially took part in the Islamic State and held some posts in the government. Soon, however, conflict broke out between the Hazara Hezbe Wahdat of Mazari and the Pashtun Ittihad-i Islami of Abdul Rasul Sayyaf.[11][12][13] The Islamic State's defense minister Ahmad Shah Massoud tried to mediate between the factions with some success, but the cease-fire remained only temporary. In June 1992, the Hezbe Wahdat and the Ittihad-i Islami engaged in violent street battles against each other. With the support of Saudi Arabia,[12] Sayyaf's forces repeatedly attacked the western suburbs of Kabul resulting in heavy civilian casualties. Likewise, Iran allegedly supported Mazari's forces that were also accused of attacking civilian targets in the west.[14] Mazari acknowledged taking Pashtun civilians as prisoners, but defended the action by saying that Sayyaf's forces took Hazaras first.[15] Mazari's group started cooperating with Hekmatyar's group from January 1993.[16]

Death

On March 12, 1995, the Taliban requested a meeting with Mazari and a delegation from the Islamic Wahdat Central Party Abuzar Ghaznawi, Ekhlaasi, Eid Mohammad Ibrahimi Behsudi, Ghassemi, Jan Mohammad, Sayed Ali Alavi, Bahodari, and Jan Ali in Chahar Asiab, near Kabul.[17] On their arrival, the group was abducted and tortured. The following day Mazari was killed and his body was found in a district of Ghazni. The Taliban issued a statement that Mazari had attacked the Taliban guards while being flown to Kandahar. Later, his body and those of his companions were handed over to Hezb-e Wahdat, mutilated and showing signs of torture.

Mazari's body was carried on foot from Ghazni to Mazar-i-Sharif in the north (at the time under the control of his ally Abdul Rashid Dostum) all across the Hazara lands in heavy snow by his followers over forty days. Hundreds of thousands attended his funeral in Mazar-i Sharif. Mazari was officially named a Martyr for National Unity of Afghanistan by President Ashraf Ghani in 2016 [6][5] and earlier by the people of Afghanistan.

References

- "Biography of Abdul Ali Mazari". 2 April 2018.

- "Afghanistan Online: Biography (Abdul Ali Mazari)". Afghan-web.com. 13 March 1995. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- "Afghanistan rocked by northern bombing". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Mazari, Abdul Ali (1995 (1374 AH)) Iḥyā-yi huvyyat: majmū‘ah-’i sukhanrānīha-yi shahīd-i mazlūm ... Ustād ‘Abd ‘Ali Mazāri (rah) (Resurrecting Identity: The collected speeches of Abdul Ali Mazari) Cultural Centre of Writers of Afghanistan, Sirāj, Qum, Iran, OCLC 37243327

- "Taliban destroy statue of foe, stoking fears after moderation claims". United States: New York Post. 18 August 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Taliban replace statue of Hazara leader in Bamiyan with Koran". France 24. 11 November 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Taliban face stiff resistance in several provinces; violence breaks out in Pashtun-dominated Jalalabad". The Week. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- "The Hazaras – Afghanistan's oppressed minority". Morning Star. 22 August 2019.

- Zucchino, David; Faizi, Fatima (27 March 2019). "They Are Thriving After Years of Persecution but Fear a Taliban Deal". The New York Times.

- "'It's inhumane': Hazara react after 63 killed in targeted ISIS attack". Public Radio International.

- "Blood-Stained Hands, Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity". Human Rights Watch. 6 July 2005.

- Amin Saikal (2006). Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival (1st ed.). London New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. p. 352. ISBN 1-85043-437-9.

- Gutman, Roy (2008): How We Missed the Story: Osama Bin Laden, the Taliban and the Hijacking of Afghanistan, Endowment of the United States Institute of Peace, 1st ed., Washington DC.

- "Afghanistan: Blood-Stained Hands: III. The Battle for Kabul: April 1992-March 1993". www.hrw.org.

- "Afghanistan: Blood-Stained Hands: III. The Battle for Kabul: April 1992-March 1993". www.hrw.org.

- "Afghanistan: Blood-Stained Hands: III. The Battle for Kabul: April 1992-March 1993". www.hrw.org.

- "Father of Hazara Nation - Abdul Ali Mazari". www.hazara.net. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

External links

- Tabaro-Baghe-Gole-Sorkh – Poetry about Abdul Ali Mazari at BabaMazary.blogfa.com

- Picture gallery at Picasaweb

- Biography of Abdul Ali Mazari