Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardian period, and its later half overlaps with the first part of the Belle Époque era of Continental Europe.

| Victorian era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1837–1901 | |||

Queen Victoria in 1859 by Winterhalter | |||

| Monarch(s) | Victoria | ||

| Leader(s) | |||

| |||

| History of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

|

| Periods in English history |

|---|

| Timeline |

| History of Scotland |

|---|

|

|

|

Various liberalising political reforms took place in the UK including expanding the electoral franchise. The Great Famine caused mass death in Ireland early in the period. The British empire had relatively peaceful relations with the other great powers. It participated in various military conflicts mainly against minor powers. The British empire expanded during this period and was the predominant power in the world.

Victorian society valued a high standard of personal conduct which reflected across all sections of society. The emphasis on morality gave impetus to social reform but also placed restrictions on the liberty of certain groups. Prosperity rose during the period. Literacy and childhood education became near universal in Great Britain for the first time. Whilst some attempts were made to improve living conditions, slum housing and disease remained a severe problem.

The period saw significant scientific and technological development. Britain was advanced in industry and engineering in particular, but somewhat undeveloped in art, education and initially science. The population of Britain increased rapidly, whilst, the population of Ireland fell sharply.

Terminology and periodisation

In the strictest sense, the Victorian era covers the duration of Victoria's reign as Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, from her accession on 20 June 1837—after the death of her uncle, William IV—until her death on 22 January 1901, after which she was succeeded by her eldest son, Edward VII. Her reign lasted for 63 years and seven months, a longer period than any of her predecessors. The term 'Victorian' was in contemporaneous usage to describe the era.[1] The era has also been understood in a more extensive sense as a period that possessed sensibilities and characteristics distinct from the periods adjacent to it, in which case it is sometimes dated to begin before Victoria's accession—typically from the passage of or agitation for (during the 1830s) the Reform Act 1832, which introduced a wide-ranging change to the electoral system of England and Wales. Definitions that purport a distinct sensibility or politics to the era have also created scepticism about the worth of the label "Victorian", though there have also been defences of it.[2]

Michael Sadleir was insistent that "in truth, the Victorian period is three periods, and not one".[3] He distinguished early Victorianism – the socially and politically unsettled period from 1837 to 1850[4] – and late Victorianism (from 1880 onwards), with its new waves of aestheticism and imperialism,[5] from the Victorian heyday: mid-Victorianism, 1851 to 1879. He saw the latter period as characterized by a distinctive mixture of prosperity, domestic prudery, and complacency[6] – what G. M. Trevelyan similarly called the "mid-Victorian decades of quiet politics and roaring prosperity".[7]

Political and diplomatic history

Domestically, Britain liberalised and gradually evolved into a democracy. The Reform Act[note 1], which made various changes to the electoral system including expanding the franchise, had been passed in 1832.[8] The franchise was expanded again by the Second Reform Act[note 2] in 1867.[9] Cities were given greater political autonomy and the labour movement was legalised.[10] From 1845 to 1852, the Great Famine caused mass starvation, disease and death in Ireland, sparking large-scale emigration.[11] The Corn Laws were repealed in response to this.[12] Across the British Empire reform included rapid expansion, the complete abolition of slavery in the African possessions, the end of transportation of convicts to Australia, loosening restrictions on colonial trade, and introducing responsible (i.e. semi-autonomous) government.[13][14]

The period from 1815 to 1914 is known as the Pax Britannia. A period of relatively peaceful relations between the world's Great Powers. This is particularly true of Britain's interactions with the others.[13] The only case of the empire participating in a war against another major power is the Crimean War from 1853 to 1856.[15][13] There were various revolts and violent conflicts within the British empire.[13][14] Britain participated in wars against minor powers.[16][13][13][14][13] It also took part in the diplomatic struggles of the Great Game[16] and the Scramble for Africa.[13][14]

In 1840, Queen Victoria married her German cousin Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfield. The couple had nine children who themselves married into various royal families and the queen thus became known as the "grandmother of Europe".[17][10] In 1861, Prince Albert died.[16] Queen Victoria went into mourning and withdrew from public life for ten years.[10] In 1871, with republican sentiments growing in Britain, the Queen began to return to public life.[17] In her later years, her popularity soared as she became a symbol of the British Empire.[17] Queen Victoria died on 22 January 1901.[17]

Society and culture

The era saw a rapidly growing middle class who became an important cultural influence to a significant extent replacing the aristocracy as the dominant class in British society.[18][19] A distinctive middle class lifestyle developed which reflected on what was valued by society as a whole.[18][20] Increased importance was placed on the value of the family and the idea that marriage should be based on romantic love gained popularity.[21][22] A clear separation was established between the home and the workplace which had often not been the case before.[20] The home was seen as a private environment,[20] where housewives provided their husbands with a rest-bite from the troubles of the outside world.[21] Within this ideal, women were expected to focus on domestic matters and rely on men as breadwinners.[23][24] Women had limited legal rights in most areas of life and a feminist movement developed.[24][25] Whilst parental authority was seen as important children were given legal protections against abuse and neglect for the first time.[26]

The growing middle class and strong evangelical movement placed great emphasis on a respectable and moral code of behaviour which included features such as charity, personal responsibility, controlled habits, child discipline and self criticism.[19][27] As well as personal improvement, importance was given to social reform.[28] Utilitarianism was another philosophy which saw itself as based on science rather than morality, but also placed emphasis on social progress.[29][30] An alliance formed between these two ideological strands.[31] The causes the reformers emphasised included improving the conditions of women and children, giving police reform priority over harsh punishment to prevent crime, religious equality and political reform in order to establish a democracy.[32] The political legacy of the reform movement was to link the nonconformists (a part of the evangelical movement) in England and Wales with the Liberal Party.[33] This continued up until the First World War.[34] The Presbyterians played a similar role as a religious voice for reform in Scotland.[35]

Religion was politically controversial during this era with Nonconformists pushing for the disestablishment of the Church of England.[36] Nonconformists, who comprised about half of church attendees in 1851,[37] gradually had the legal discrimination which had been established against them outside of Scotland removed.[38][39][40][41] Legal restrictions on Catholics were also largely removed. The number of Catholics grew in Great Britain due to conversions and immigration from Ireland.[36] Secularism and doubts about the accuracy of the Old Testament grew among people with higher levels of education during this time period.[42] Northern English and Scottish academics tended to be more religiously conservative, whilst agnosticism and even atheism (though its promotion was illegal[43]) gained appeal among academics in the south.[44] Historians refer to a "Victorian Crisis of Faith" as a period where religious views had to readjust to suit new scientific knowledge and criticism of the bible.[45]

Access to education increased rapidly during the 19th century. State funded schools were established in England and Wales for the first time. Education became compulsory for pre-teenaged children in England, Scotland and Wales. Literacy rates increased rapidly nearing universal levels by the end of the century.[46][47] Private education for wealthier children, both boys and more gradually girls, became more formalised over the course of the century.[46] A variety of reading materials grew in popularity during the period.[48][49][50][1][51][48][52][53] Other popular forms of entertainment included brass bands,[54] circuses,[55] "spectacles" (alleged paranormal activities),[56] amateur nature collecting,[57][58] gentlemen's clubs for wealthier men,[59] and seaside holidays for the middle class.[60] Many sports were introduced or popularised during the Victorian era.[61] They became important to male identity.[62] Popular sports of the period included cricket,[63] cycling, croquet, horse-riding, and many water activities.[64] Opportunities for leisure increased as restrictions were placed on maximum working hours, wages increased and routine annual leave became increasingly common.[65][66]

Economy, industry, and trade

Prior to the industrial revolution, daily life had changed little for hundreds of years. The 19th century saw rapid technological development with a wide range of new inventions being developed.[67] This technological advancement led to Great Britain becoming the foremost industrial and trading nation of the time.[68] Historians have characterised the mid-Victorian era (1850–1870) as Britain's "Golden Years",[69][70] with national income per person increasing by half. This prosperity was driven by increased industrialisation, especially in textiles and machinery along with exports to the empire and elsewhere.[71] The positive economic conditions, as well as a fashion among employers for providing welfare services to their workers led to relative social stability.[71][72] Government involvement in the economy was limited.[72] It wasn't until the post-World War II period around a century later that the country experienced substantial economic growth again.[70] However, whilst industry was well developed, education and the arts were mediocre.[72] Historian Llewellyn Woodward concluded that whilst the quality of life was improving by the "golden years" conditions and housing for the working classes "were still a disgrace to an age of plenty."[73] Wage rates continued to improve in the later 19th century; real wages (after taking inflation into account) were 65 percent higher in 1901, compared to 1871. Much of the money was saved, as the number of depositors in savings banks rose from 430,000 in 1831, to 5.2 million in 1887, and their deposits from £14 million to over £90 million.[74]

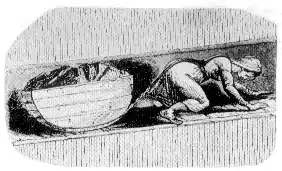

19th-century Britain saw a huge population increase accompanied by rapid urbanisation stimulated by the Industrial Revolution.[74] The rapid growth in population in the 19th century in the cities included the new industrial and manufacturing cities, as well as service centres such as Edinburgh and London.[75][76] Private renting from housing landlords was the dominant tenure. P. Kemp says this was usually of advantage to tenants.[77] People moved in so rapidly that there was not enough capital to build adequate housing for everyone, so low income newcomers squeezed into increasingly overcrowded slums. Clean water, sanitation, and public health facilities were inadequate; the death rate was high, especially infant mortality, and tuberculosis among young adults. Cholera from polluted water and typhoid were endemic. Unlike rural areas, there were no famines such as the one which devastated Ireland in the 1840s.[78][79][80] Conditions were particularly bad in London, where the population rose sharply and poorly maintained, overcrowded dwellings became slum housing. Kellow Chesney wrote of the situation that:[81]

Hideous slums, some of them acres wide, some no more than crannies of obscure misery, make up a substantial part of the metropolis... In big, once handsome houses, thirty or more people of all ages may inhabit a single room

The early Victorian era before the reforms of the 1840s became notorious for the employment of young children in factories and mines and as chimney sweeps.[82][83] The children of the poor were expected to help towards the family budget, often working long hours in dangerous jobs for low wages.[81] Reformers wanted the children in school: in 1840 only about 20 percent of the children in London had any schooling.[84] By the 1850s, around half of the children in England and Wales were in school (not including Sunday school).[46] From the 1833 Factory Act onwards, attempts were made to get child labourers into part time education though these were often difficult to enforce in practise.[85] It was only in the 1870s and 1880s that children began to be compelled into school.[46]

Knowledge and public health

The professionalisation of scientific study began in parts of Europe following the French Revolution but was slow to reach Britain. William Whewell coined the term scientist in 1833 to refer to those who studied what was generally then known as natural philosophy but it look a while to catch on. Having been previously dominated by amateurs with a separate income, the Royal society began to solely admit professionals from 1847 onwards. Biologist Thomas Huxley indicated in 1852 that it remained difficult to earn a living through being a scientist alone.[44] The Victorians respected science seeing it as something which could improve society and being a scientist was a prestigious occupation.[86][87][44] Significant advancements took place in various fields of research including statistics,[88] elasticity,[89] refrigeration,[90] natural history,[44] electricity[91] and logic.[92]

Britain was advanced in engineering and technology.[86][87] The Victorian era saw methods of communication and transportation develop significantly. In 1837, William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone invented the first telegraph system. This system which used electrical currents to transmit coded messages quickly spread across Britain, appearing in every town and post office. A worldwide network developed towards the end of the century. In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone. A little over a decade later, 26,000 telephones were in service in Britain. Multiple switchboards were installed in every major town and city.[93] Guglielmo Marconi developed early radio broadcasting at the end of the period.[94] The railways were important economically in the Victorian era allowing goods, raw materials, and people to be moved around stimulating trade and industry.[95] Britain's engineers were contracted around the world to build railways.[86][87] Financing railways around the world became a speciality of London's financiers. They maintained an ownership share in these railways which were ultimately largely liquidated in the early part of the First World War to contribute to the war effort.[95][95]

Improvements were made over time to housing along with the management of sewage and water.[96][97] A gas network for lighting and heating was introduced in the 1880s.[96] Medicine advanced rapidly during the 19th century and germ theory was developed for the first time.[97] Doctors became more specialised and the number of hospitals grew.[97] In spite of this, the mortality rate fell only marginally, from 20.8 per thousand in 1850 to 18.2 by the end of the century. Urbanisation aided the spread of diseases and squalid living conditions in many places exacerbated the problem.[97] Britain experienced rapid population growth during the Victorian era.[98] The population of England, Scotland and Wales grew rapidly during the 19th century.[99][100] Various factors are considered contributary to this including rising fertility rate,[101] falling infant mortality,[67] the lack of a catastrophic pandemic or famine in the island of Great Britain during the 19th century for the first time in history,[102] improved nutrition,[102] and a lower overall mortality rate.[102] The population of Ireland shrank significantly mostly due to emigration and the Great Famine.[103]

Moral standards

Expected standards of personal conduct changed in around the first half of the 19th century with good manners and self restraint becoming much more common.[104] Historians have suggested various contributing factors, such as the major conflicts with France Britain participated in during the early 19th century meaning that the distracting temptations of sinful behaviour had to be avoided in order to focus on the war effort and the evangelical movement's push for moral improvement.[105] There is evidence that the expected standards of moral behaviour were reflected in action as well as rhetoric across all classes of society.[106][107] For instance, an analysis suggested that less than 5% of working class couples co-habited before marriage.[106]

Legal restrictions were placed on cruelty to animals.[108][109][110] Restrictions were placed on the working hours of child labourers on the 1830s and 1840s.[111][112] Further interventions took place throughout the century to increase the level of child protection.[113] Contrary to popular conception, Victorian society understood that both men and women enjoyed copulation.[114] The development of police forces led to a rise in prosecutions for illegal sodomy in the middle of the 19th century.[115] Male sexuality became a favorite subject of study by medical researchers.[116] All male homosexual acts were made illegal for the first time.[117] At a time when there were relatively few job options for women, some particularly poorer women without familial support, took to prostitution to support themselves.[118] Estimates vary, but in his landmark study, Prostitution, William Acton reported an estimation of 8,600 prostitutes in London alone in 1857.[119] Whilst this caused a moral panic in some sections of public life, there were some dissenting voices at the time. Women suspected of prostitution were for a period between the 1860s and 1880s subject to spot compulsory examinations for STDs and detainment if they were found to be infected.[118]

See also

Bibliography of the Victorian era - List of relevant works

References

- Plunkett, John; et al., eds. (2012). Victorian Literature: A Sourcebook. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 2.

- Hewitt, Martin (Spring 2006). "Why the Notion of Victorian Britain Does Make Sense". Victorian Studies. 48 (3): 395–438. doi:10.2979/VIC.2006.48.3.395. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- M Sadleir, Trollope (London 1945) p. 17

- M Sadleir, Trollope (London 1945) p. 18-19

- M Sadleir, Trollope (London 1945) p. 13 and p. 32

- M Sadleir, Trollope (London 1945) pp. 25–30

- G M Trevelyan, History of England (London 1926) p. 650

- Swisher, Clarice, ed. Victorian England. San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 2000. pp. 248–250

- "Notes Upon 'the Representation of the People Act, 1867' (30 & 31 Vict. C. 102.): With Appendices Concerning the Antient Rights, the Rights Conferred by the 2 & 3 Will. IV C. 45, Population, Rental, Rating, and the Operation of the Repealed Enactments as to Compound Householders", Thomas Chisholm Anstey, pp. 26, 169–172.

- National Geographic (2007). Essential Visual History of the World. National Geographic Society. pp. 290–92. ISBN 978-1-4262-0091-5.

- Kinealy, Christine (1994), This Great Calamity, Gill & Macmillan, p. xv

- Lusztig, Michael (July 1995). "Solving Peel's Puzzle: Repeal of the Corn Laws and Institutional Preservation". Comparative Politics. 27 (4): 393–408. doi:10.2307/422226. JSTOR 422226.

- J. Holland Rose et al. eds. The Cambridge History of the British Empire Vol-ii: The Growth of the New Empire 1783–1870 (1940) pp v–ix. online

- E.A. Benians et al. eds. The Cambridge History of the British Empire Vol. iii: The Empire – Commonwealth 1870–1919' (1959) pp 1–16. online

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1954). The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848–1918. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS, MUMBAI. pp. 60–61.

- Swisher, ed., Victorian England, pp. 248–50.

- "Queen Victoria: The woman who redefined Britain's monarchy". BBC Teach. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Houghton, The Victorian Frame of Mind, p. 1

- On the interactions of evangelicalism and utilitarianism see Élie Halévy, A History of the English People in 1815 (1924) 585–95; also 3:213–15.

- Wohl, Anthony S. (1978). The Victorian family: structure and stresses. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 9780856644382.

- Cited in: Summerscale, Kate (2008). The suspicions of Mr. Whicher or the murder at Road Hill House. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 109–110. ISBN 9780747596486. (novel)

- K. Theodore Hoppen, The mid-Victorian generation, 1846–1886 (2000), pp 316ff.

- Boston, Michelle (12 February 2019). "Five Victorian paintings that break tradition in their celebration of love". USC Dornsife. University of Southern California. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Robyn Ryle (2012). Questioning gender: a sociological exploration. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE/Pine Forge Press. pp. 342–43. ISBN 978-1-4129-6594-1.

- Susan Rubinow Gorsky, Femininity to Feminism: Women and Literature in the Nineteenth Century (1992)

- Gray, F. Elizabeth (2004). ""Angel of the House" in Adams, ed". Encyclopedia of the Victorian Era. 1: 40–41.

- "A history of child protection". A history of child protection. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- G.M. Young, Victorian England: Portrait of an Age (1936, 2nd ed, 1953), pp 1–6.

- Asa Briggs, The Age of Improvement 1783–1867 (1957) pp 236–85.

- John Roach, "Liberalism and the Victorian Intelligentsia." Cambridge Historical Journal 13#1 (1957): 58–81. online.

- Young, Victorian England: Portrait of an Age pp 10–12.

- On the interactions of evangelicalism and utilitarianism see Élie Halévy, A History of the English People in 1815 (1924) 585–95; see pp 213–15.

- Llewellyn Woodward, The Age of Reform, 1815–1870 (1962), pp 28, 78–90, 446, 456, 464–65.

- D. W. Bebbington, The Nonconformist Conscience: Chapel and Politics, 1870–1914 (George Allen & Unwin, 1982)

- Glaser, John F. (1958). "English Nonconformity and the Decline of Liberalism". The American Historical Review. 63 (2): 352–363. doi:10.2307/1849549. JSTOR 1849549.

- Wykes, David L. (2005). "Introduction: Parliament and Dissent from the Restoration to the Twentieth Century". Parliamentary History. 24 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1750-0206.2005.tb00399.x.

- Owen Chadwick, The Victorian church (1966) 1:7–9, 47–48.

- Sally Mitchell, Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia (2011), p 547

- G. I. T. Machin, "Resistance to Repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, 1828." Historical Journal 22#1 (1979): 115–139.

- Davis, R. W. (1966). "The Strategy of "Dissent" in the Repeal Campaign, 1820–1828". The Journal of Modern History. 38 (4): 374–393. doi:10.1086/239951. JSTOR 1876681. S2CID 154716174.

- Olive Anderson, "Gladstone's Abolition of Compulsory Church Rates: a Minor Political Myth and its Historiographical Career." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 25#2 (1974): 185–198.

- Richard Helmstadter, "The Nonconformist Conscience" in Peter Marsh, ed., The Conscience of the Victorian State (1979) pp 144–47.

- "Coleridge's Religion". victorianweb.org. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church: Vol 1 1829–1859 (1966) pp 487–89.

- Lewis, Christopher (2007). "Chapter 5: Energy and Entropy: The Birth of Thermodynamics". Heat and Thermodynamics: A Historical Perspective. United States of America: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33332-3.

- Eisen, Sydney (1990). "The Victorian Crisis of Faith and the Faith That was Lost". In Helmstadter, Richard J.; Lightman, Bernard (eds.). Victorian Faith in Crisis: Essays on Continuity and Change in Nineteenth-Century Religious Belief. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 2–9. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-10974-6_2. ISBN 9781349109746.

- Lloyd, Amy (2007). "Education, Literacy and the Reading Public" (PDF). University of Cambridge.

- "15 Crucial Events in the History of English Schools". Oxford Royale. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- "Aspects of the Victorian book: Magazines for Women". British Library. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- "Aspects of the Victorian book: the novel". British Library. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- McGillis, Roderick (6 May 2016). "Children's Literature - Victorian Literature". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- John, Juliet, ed. (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Literary Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–2.

- "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- Hazel Conway, People's parks: the design and development of Victorian parks in Britain (Cambridge University Press, 1991)

- Brenda Assael, The circus and Victorian society (U of Virginia Press, 2005)

- Alison Winter, Mesmerized: powers of mind in Victorian Britain (U of Chicago Press, 2000)

- Lynn L. Merrill, The romance of Victorian natural history (Oxford University Press, 1989)

- Simon Naylor, "The field, the museum and the lecture hall: the spaces of natural history in Victorian Cornwall." Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers (2002) 27#4 pp: 494–513. online Archived 17 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Peter Bailey, Leisure and class in Victorian England: Rational Recreation and the contest for control, 1830–1885 (Routledge, 2014)

- John K. Walton, The English seaside resort. A social history 1750–1914 (Leicester University Press, 1983)

- William J. Baker, "The state of British sport history". Journal of Sport History 10.1 (1983): 53–66. online Archived 12 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Maguire, Joe (1986). "Images of manliness and competing ways of living in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain". International Journal of the History of Sport. 3 (3): 265–287. doi:10.1080/02649378608713604.

- Keith A. P. Sandiford, Cricket and the Victorians (Routledge Press, 1994).

- "Victorian Games & Sports, Tennis, Cricket, Football, Croquet, Cycling" in Victorian-Era.org Online Archived 6 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- G. R. Searle, A New England?: Peace and War, 1886–1918 (Oxford University Press, 2004), 529–70.

- Hugh Cunningham, Time, work and leisure: Life changes in England since 1700 (2014)

- Dutton, Edward; Woodley of Menie, Michael (2018). "Chapter 7: How Did Selection for Intelligence Go Into Reverse?". At Our Wits' End: Why We're Becoming Less Intelligent and What It Means for the Future. Great Britain: Imprint Academic. pp. 85, 95–6. ISBN 9781845409852.

- Atterbury, Paul (17 February 2011). "Victorian Technology". BBC History. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Bernard Porter, Britannia's Burden: The Political Evolution of Modern Britain 1851–1890 (1994) ch 3

- Hobsbawn, Eric (1995). "Chapter Nine: The Golden Years". The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century 1914-1991. Abacus. ISBN 9780349106717.

- F. M. L. Thompson, Rise of Respectable Society: A Social History of Victorian Britain, 1830–1900 (1988) pp. 211–214.

- Porter, ch. 1–3; K Theodore Hoppen, The Mid-Victorian Generation: 1846–1886 (1998), ch 1 to 3, 9–11

- Llewellyn Woodward, The Age of Reform, 1815–1870 (2nd ed. 1962) p 629

- J. A. R. Marriott, Modern England: 1885–1945 (4th ed., 1948) p 166.

- Dyos, H. J. (1968). "The Speculative Builders and Developers of Victorian London". Victorian Studies. 11: 641–690. JSTOR 3825462.

- Christopher Powell, The British building industry since 1800: An economic history (Taylor & Francis, 1996).

- Kemp, P. (1982). "Housing landlordism in late nineteenth-century Britain". Environment and Planning A. 14 (11): 1437–1447. doi:10.1068/a141437. S2CID 154957991.

- Dyos, H. J. (1967). "The Slums of Victorian London". Victorian Studies. 11 (1): 5–40. JSTOR 3825891.

- Anthony S. Wohl, The eternal slum: housing and social policy in Victorian London (1977).

- Martin J. Daunton, House and home in the Victorian city: working class housing, 1850–1914 (1983).

- Barbara Daniels, Poverty and Families in the Victorian Era Archived 6 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Jane Humphries, Childhood & Child Labour in The British Industrial Revolution (Cambridge UP, 2016).

- Del Col, Laura (1988). "The Life of the Industrial Worker in Ninteenth-Century [sic] England". The Victorian Web. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Child Labor Archived 21 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine David Cody, Hartwick College

- May, Trevor (1994). The Victorian Schoolroom. Great Britain: Shire Publications. pp. 3, 29.

- Lionel Thomas Caswell Rolt, Victorian engineering (Penguin, 1974).

- Herbert L. Sussman, Victorian technology: invention, innovation, and the rise of the machine (ABC-CLIO, 2009)

- Katz, Victor (2009). "Chapter 23: Probability and Statistics in the Nineteenth Century". A History of Mathematics: An Introduction. Addison-Wesley. pp. 824–30. ISBN 978-0-321-38700-4.

- Kline, Morris (1972). "28.7: Systems of Partial Differential Equations". Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times. United States of America: Oxford University Press. pp. 696–7. ISBN 0-19-506136-5.

- Lewis, Christoper (2007). "Chapter 7: Black Bodies, Free Energy, and Absolute Zero". Heat and Thermodynamics: A Historical Perspective. United States of America: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33332-3.

- Baigrie, Brian (2007). "Chapter 8: Forces and Fields". Electricity and Magnetism: A Historical Perspective. United States of America: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33358-3.

- Katz, Victor (2009). "21.3: Symbolic Algebra". A History of Mathematics: An Introduction. Addison-Wesley. pp. 738–9. ISBN 978-0-321-38700-4.

- Baigrie, Brian (2007). "Chapter 10: Electromagnetic Waves". Electricity and Magnetism: A Historical Perspective. United States of America: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33358-3.

- John R. Kellett, The impact of railways on Victorian cities (Routledge, 2007).

- Anthony S. Wohl, Endangered lives: public health in Victorian Britain (JM Dent and Sons, 1983)

- Robinson, Bruce (17 February 2011). "Victorian Medicine – From Fluke to Theory". BBC History. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- "Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population: Library of Economics"

- The UK and future Archived 15 February 2006 at the UK Government Web Archive, Government of the United Kingdom

- A. K. Cairncross, The Scottish Economy: A Statistical Account of Scottish Life by Members of the Staff of Glasgow University (Glasgow: Glasgow University Press, 1953), p. 10.

- Simon Szreter, Fertility, class and gender in Britain, 1860–1940 (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- Szreter, Simon (1988). "The importance of social intervention in Britain's mortality decline c.1850–1914: A re-interpretation of the role of public health". Social History of Medicine. 1: 1–37. doi:10.1093/shm/1.1.1. S2CID 34704101. (subscription required)

- "Ireland – Population Summary". Homepage.tinet.ie. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- Harold Perkin, The Origins of Modern English Society (1969) p. 280.

- Asa Briggs, The Age of Improvement: 1783–1867 (1959), pp. 66–74, 286–87, 436

- Rebecca Probert, "Living in Sin", BBC History Magazine (September 2012); G. Frost, Living in Sin: Cohabiting as Husband and Wife in Nineteenth-Century England (Manchester U.P. 2008)

- Ian C. Bradley, The Call to Seriousness: The Evangelical Impact on the Victorians (1976) pp. 106–109

- "London Police Act 1839, Great Britain Parliament. Section XXXI, XXXIV, XXXV, XLII". Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- M. B. McMullan, "The Day the Dogs Died in London" The London Journal: A Review of Metropolitan Society Past and Present (1998) 23#1 pp 32–40 https://doi.org/10.1179/ldn.1998.23.1.32

- Rothfels, Nigel (2002), Representing Animals, Indiana University Press, p. 12, ISBN 978-0-253-34154-9. Chapter: 'A Left-handed Blow: Writing the History of Animals' by Erica Fudge

- Georgina Battiscombe, Shaftesbury: A Biography of the Seventh Earl 1801–1885 (1988) pp. 88–91.

- Kelly, David; et al. (2014). Business Law. Routledge. p. 548. ISBN 9781317935124.

- C. J. Litzenberger; Eileen Groth Lyon (2006). The Human Tradition in Modern Britain. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 142–43. ISBN 978-0-7425-3735-4.

- Draznin, Yaffa Claire (2001). Victorian London's Middle-Class Housewife: What She Did All Day (#179). Contributions in Women's Studies. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-313-31399-8.

- Sean Brady, Masculinity and Male Homosexuality in Britain, 1861–1913 (2005).

- Ivan Crozier, "Nineteenth-century British psychiatric writing about homosexuality before Havelock Ellis: The missing story." Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 63#1 (2008): 65–102.

- F. Barry Smith, "Labouchere's amendment to the Criminal Law Amendment bill." Australian Historical Studies 17.67 (1976): 165–173.

- Walkowitz, Judith (1980). Prostitution and Victorian Society. Cambridge University Press.

- Acton, William (1857). Prostitution Considered in its Moral, Social, and Sanitary Aspects (Reprint of the Second Edition with new biographical note ed.). London: Frank Cass (published 1972). ISBN 0-7146-2414-4.

Notes

- A Scottish Reform Act and Irish Reform Act were passed separately.

- See Representation of the People (Ireland) Act 1868 and Representation of the People (Scotland) Act 1868 for equivalent reforms made in those jurisdictions