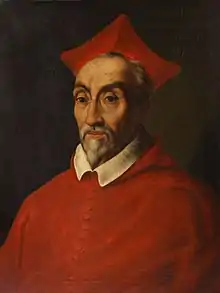

Melchior Klesl

Melchior Khlesl (Klesl,Klesel,Cleselius[1]) (19 February 1552 – 18 September 1630) was an Austrian statesman and cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church during the time of the Counter-Reformation. He was minister-favourite of King and Emperor Matthias (1609 – 1618) and a leading peace-advocate (between the different confessional leagues of the empire) in the period before the Thirty Years War. Klesl was appointed Bishop of Vienna in 1602 and elevated to cardinal in December 1615.

His Eminence the Most Reverend Melchior Cardinal Khlesl | |

|---|---|

| Cardinal-Priest of Santa Maria della Pace | |

Melchior Khlesl | |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| In office | 1624–1630 |

| Predecessor | Alessandro d'Este |

| Successor | Fabrizio Verospi |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 30 March 1614 by Placido della Marra |

Biography

Born in Vienna to Lutheran Protestant parents, with his father being a baker, Melchior Klesl studied philosophy at the University of Vienna, and converted impressed by the preaching of Jesuits. He entered the faculty of Philosophy at University of Vienna in 1570. In 1574 he joined the “Papal Alumnat”, a boarding school for prospective priests run by the Jesuits in Vienna. At this time the Emperor Rudolf II became aware of him as promising candidate for the priesthood. He wanted to use him for his plans for a campaign against his protestant noble estates and towns as well as for a church reform in Lower Austria.[2]

In 1579 Khlesl, now doctor of philosophy, was given the post of cathedral provost of St. Stephan in Vienna and he received his ordination to the priesthood.

The emperor and his advisors put the prince-bishop of Passau, Urban of Trenbach, under pressure to make Khlesl his official representative in Vienna to carry out a reform of the Catholic clergy. Trenbach, appointed Khlesl as his official representative for Lower Austria in 1580 and in 1581 as his vicar-general in Vienna. His task was to discipline the dissolute and lax catholic clergy. As cathedral provost and chancellor of the university, Khlesl worked on behalf of the emperor to make adherence to the roman-catholic confession a duty for professors and students. As an official he was also given the task by Rudolf II to bring back the protestant towns in Lower Austria to the faith of the emperor. This campaign, the “Religionsreformation”, had its high point in the years 1585 to 1588.

Khlesl’s moderate measures during his campaign to re-catholicize Lower Austria became the source of some tension with Jesuits like the hard-liner Father Georg Scherer, S.J., that soon led to an open contention. To calm things down, Khlesl claimed that Scherer was the one who convinced him to convert and that they both had the same goal. In 1588 the emperor appointed Khlesl as administrator of the Diocese of Wiener Neustadt.

Because of losing some powerful supporters such as Leonhard IV von Harrach in Vienna and Adam von Dietrichstein at the imperial court in Prague and the governor Archduke Ernst by the end of the decade the “Religionsreformation” was losing support more and more against the opposition in the government in Vienna. Even the intervention of Emperor Rudolf II didn’t help. The opposition, above all that from the chancellor Wolfgang Unverzagt, who was regarded as all powerful in the government of Archduke Matthias in Vienna, was too strong.

Unverzagt proposed making Khlesl Bishop of the small run-down Bishopric of Vienna which was intended to take the wind out of his sails. Khlesl’s allies in Prague, the privy councillors Wolf Rumpf and Paul Sixt III von Trautson, could not do anything against it. To avoid political unimportance, Khlesl sought to be named to an influential position on the staff of Archduke Matthias, but he was unsuccessful.[3] In 1598 Archduke Maximilian III, who presided over the Hungarian diet at Bratislava for his brother Matthias, announced Khlesl’s nomination as Bishop of Vienna. After a sensation, provoked by Khlesl himself, who announced, that he would run the bishopric with hard hand and in opposition to the government in Vienna, the nomination was withdrawn. But in 1602 he was installed as the nominated bishop after his demands for economic support for the bishopric were fulfilled. Klesl was named Bishop of Vienna, a diocese which was spiritually and materially in a state of degradation. On 30 Mar 1614, he was consecrated bishop by Placido della Marra, Bishop of Melfi e Rapolla.[4] He received the purple from Paul V in 1616.

His appointment as bishop of Vienna took place in a phase of high hopes in Prague, Vienna and Graz, that the catholic House of Austria will reassert its position against the protestant oppositions in the Lands of Habsburgmonarchie. Khlesl favored a confronting course against the opposition. At the same time the “Bruderzwist” (the struggle between the emperor Rudolf II and his brothers for the succession in the Habsburgmonarchie and the Roman-German Empire) sharpened. Specifically the ambition of Matthias to become emperor himself, offered Khlesl the opportunity to increase his influence at the court in Vienna. He tried to thread a marriage of Matthias to the Bavarian Princess Magdalena, for getting the Dukes of Bavaria as catholic allies in the struggle for the throwns of Rudolf II. In the end the negotiations came to nothing because Magdalena didn’t want to be his wife.

Since 1605, due to the uprising of Stefan Bocskai in Hungary and Transylvania, the emperor and Matthias as governor in Vienna had been pursuing a more moderate policy toward the protestant opposition in the estates of the Habsburgmonarchie because they needed their support against Bocskai. Khlesl opposed this policy, but the final decision lay in the hands of the council around Matthias and increasingly Karl I von Liechtenstein, privy councillor of Rudolf II and some times his High Steward. Liechtenstein increasingly dominated the politics of Archduke Matthias up to the point of a putsch against his brother, Emperor Rudolf II. Matthias took over Austria, Moravia and Hungry. But for this success he had to make, first of all advised by Liechtenstein, hard concessions to his allied estates.

In the spring 1609 Khlesl was finally able to reach the high point of his power in Vienna when he became the minister-favourite of Matthias, for beeing formally the president of privy council he had to wait until January 1613. Liechtenstein left the court. Khlesls struggle for the position of the dominate minister in Vienna, however, continued until December 1611 when Liechtenstein gave up and admitted defeat.

In 1609 Khlesl tried to withdraw the concessions made to the oppositional estates made by Liechtenstein and his supporters. But the quarrel with the emperor plus the political and economic weakness of Matthias forced Khlesl to take an increasingly more moderate stance toward the protestant opposition and even with the Calvinists. Khlesl was working to make Matthias the next emperor.

For this goal he needed the protestant Electors. The ecclesiastical (bishop) electors were in favor of Archduke Albrecht VII, brother of Matthias and ruler of the Spanish Netherlands, to be the next emperor.[5] After the death of Rudolf II, the election of Matthias succeeded thanks to the protestant vote. As the minister-favourite of the new Emperor, Khlesl at first pursued a policy of mobilizing the estates of the Roman-German Empire for a new war against the Turks, hoping to unify the hostile confessional camps under the emperor. But this move proved to be a failure.

Hence he began in 1614 to negotiate with Turkish envoys for a new peace treaty. The Treaty of Vienna in 1615 with the Turkish Empire was probably his greatest political success. His efforts to settle the conflicts among the confessional associations, Protestant Union and Catholic League, were much less successful. His attempts to dissolve the confessional alliances in order to create a party of the emperor faced insurmountable resistance.

Since the coronation of Matthias as Emperor, the question of succession immediately became an important political issue because Matthias had in his marriage with Anna of Tyrol no male heir to succeed him. The King of Spain wanted to make his son Emperor and beforehand King of Bohemia and Hungary. Archduke Ferdinand of Inner Austria also claimed these crowns and found with Maximilian III a scheming supporter. The negotiations with Philip III lasted until a treaty between Philip and Ferdinand, the Oñate treaty in the spring of 1617. The archdukes Maximilian III and Ferdinand urged the election of Ferdinand as Roman-German King before the Habsburgs reached any agreement about the crowns of Bohemia and Hungary. But Khlesl first wanted negotiations with the Calvinist Electors to save the election. Maximilian III and the catholic camp saw this as a tactic for protracting the election. So Khlesl needed protection against his enemies in the House of Austria (Casa de Austria) and the catholic camp. The device was the promotion to cardinal. Emperor Matthias pleased the pope to make Khlesl cardinal.

On December 2 1615 Pope Paul V made Melchior Khlesl in pectore Cardinal, and had it proclaimed on the April 11 1616. He received Santa Maria degli Angeli as his titular church, but 1623 switched to San Silvestro in Capite. Maximilian III had already in 1616 planned to murder Cardinal Khlesl, but his cousin Ferdinand held him back. The uprising in Bohemia (The “Fenstersturz”) which ultimately led to the beginning of the Thirty Years War, brought about the end of Khlesl’s position as minister-favourite. Reason was his preferential treatment of a moderate reaction because the emperor lacked the money for a military answer and Phillip III didn’t signal any strong assistance. On July 20, 1618 Maximilian III, Ferdinand II, now King of Bohemia and Hungary, and the Spanish ambassador Inigo Velez de Guevara, Conde de Oñate arrested Khlesl and held him prisoner in Tyrol.

The Pope sent a special envoy, Cardinal Fabrizio Verospi, to investigate Khlesl’s case. Verospi urged in the name of Paul V that the cardinal be placed under ecclesiastical arrest. In 1619 Khlesl was brought to the monastery St. Georgenberg where he was held in ecclesiastical custody and under the supervision of the government in Innsbruck. Through papal diplomacy, first of all by cardinal nephew (papal nepot) Ludovico Ludovisi, Khlesl could be transferred to Castel Sant’ Angelo in Rome on October 23, 1622 and the accusations against him were so reduced that no legitimation for his arrest remained. On June 18, 1623 Pope Gregor XV released him from custody. In Rome Khlesl carried on political activities in support for his earlier enemies Maximilian I from Bavaria and Johann Schweikhart von Cronberg, Elector of Mainz. In Vienna this policy was seen as revenge on the emperor. To get Khlesl out of Rome, Ferdinand II, now emperor, accepted full satisfaction for Cardinal Khlesl. Pope Urban VIII cleared Khlesl of any quilt and in the Autumn of 1626 he was allowed to leave Rome. On January 25, 1628 Khlesl entered the cathedral of St. Stephan in Vienna in a festive procession and resumed his episcopate. Though the catholic alliance seemed to be very successful in the war against the protestant princes and their allies, Ferdinand II, influenced by his Jesuit confessor Wilhelm Lamormaini, wanted to exploit the victories to continue to push protestant princes back as far as possible; but Khlesl held to his conviction that the war could not be won and it would be better for the emperor and the Roman Catholic Church to proceed more prudently.

He died in Wiener Neustadt in 1630. His heart reposes before the high altar of the cathedral of Wiener Neustadt while his body rests in the cathedral of St. Stephen's, Vienna.

Inhabitants of Vienna will recognize Klesl's name first and foremost because Khleslplatz (Khlesl Square) in Vienna's 12th district, Meidling, in the former village of Altmannsdorf, has been named after the cardinal, allegedly because he used to stop at No.12 on his journeys from Wiener Neustadt to Vienna. Since 1978, the 16th century building has housed the Renner-Institut, the political academy of the Social Democratic Party of Austria, while No.6 was, until 1998, the site of the Tierschutzhaus of the Wiener Tierschutzverein (founded in 1846), where generations of animal lovers would go to collect homeless pets.

Episcopal succession

While bishop, he was the principal consecrator of:[4]

- Péter Pázmány, Archbishop of Esztergom (1617);

- Lilio Livioi, Auxiliary Bishop of Constantinople (1625);

- Vincenzo Martinelli (bishop), Bishop of Conversano (1625); and

- Giovanni Battista Maria Pallotta, Titular Archbishop of Thessalonica (1628).

References

- He uses the spelling Khlesl himself in his German-language correspondence: Victor Bibl, Klesl's Briefe an K. Rudolfs II. Obersthofmeister Adam Freiherrn von Dietrichstein (1583-1589). Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte Klesl's und der Gegenreformation in Niederösterreich, in: Archiv für österreichische Geschichte 88 (1900) 473-580.

- Haberer, Ohnmacht und Chance 210ff.

- Haberer, Kardinal Khlesl 110ff.

- "Melchior Cardinal Klesl " Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney. Retrieved December 17, 2016

- Duerloo, Luc (2012). Dynasty and Piety: Archduke Albert (1598-1621) and Habsburg Political Culture in an Age of Religious Wars. Farnham. pp. 259f. et pas. ISBN 9780754669043.

Further reading

- Michael Haberer: Ohnmacht und Chance. Leonhard von Harrach (1514–1590) und die erbländische Machtelite (= Mitteilungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung, Ergänzungsband 56). Wien/München 2011.

- Michael Haberer: Kardinal Khlesl. Der Richelieu des Kaiser. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2022, ISBN 978-3-7543-0315-3.

- Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, Khlesl's, des Cardinals, Directors des geheimen Cabinetes Kaiser Mathias, Leben. Mit der Sammlung von Khlesl's Briefen und anderen Urkunden (4 vols., Vienna, 1847-1851).

- Anton Kerschbaumer, Kardinal Klesl (Vienna, 1865; 2nd ed., 1905).

- Klesls Briefe an Rudolfs II. Obersthofmeister A. Freiherr von Dietrichstein, edited by Viktor Bibl (Vienna, 1900).

External links

- Hugo Altmann (1992). "Klesl (Cleselius, Khlesl, Klesel), Melchior". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 4. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 42–45. ISBN 3-88309-038-7.