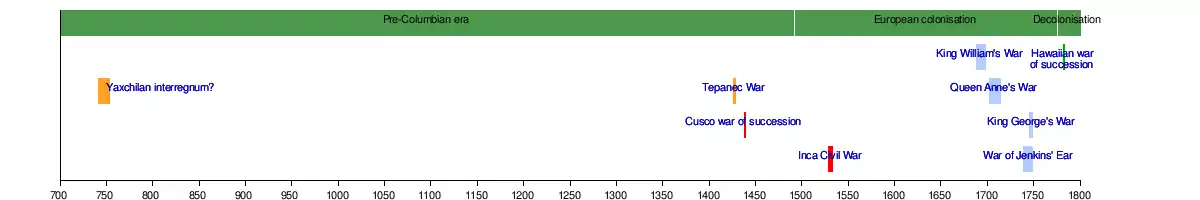

List of wars of succession

This is a list of wars of succession.

Note: Wars of succession in transcontinental states are mentioned under the continents where their capital city was located. Names of wars that have been given names by historians are capitalised; the others, whose existence has been proven but not yet given a specific name, are provisionally written in lowercase letters (except for the first word, geographical and personal names).

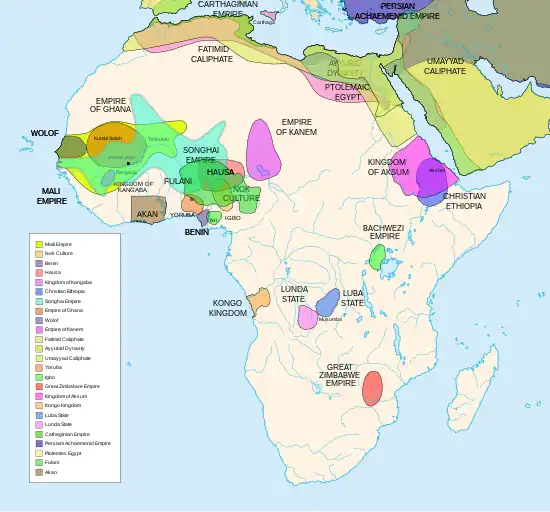

Africa

- Egypt

- North Africa

- West Africa

- Central and Southern Africa

- East Africa

- Ancient Egyptian wars of succession[2]

- Wars of the Diadochi or Wars of Alexander's Successors (323–277 BCE), after the death of king Alexander the Great of Macedon[3]

- Numidian war of succession (118–112 BCE), after the death of king Micipsa of Numidia; this spilled over into the Roman–Numidian Jugurthine War (112–106 BCE)

- Revolt of Nizar (1094–1095), after the death of caliph Al-Mustansir Billah of the Fatimid Caliphate

- Almohad war of succession (1224), after the death of caliph Yusuf al-Mustansir of the Almohad Caliphate[4]

- Hafsid war of succession and Marinid invasion (1346–1347), after the death of caliph Abu Yahya Abu Bakr II of the Hafsid dynasty[5]

- Malian war of succession (1360), after the death of mansa Suleyman of the Mali Empire[6]

- Sayfawa war of succession (c. 1370), after the death of mai Idris I Nigalemi (Nikale) of the Kanem–Bornu Empire (Sefuwa or Sayfawa dynasty) between his brother Daud (Dawud) and his son(s), because it was unclear whether collateral (brother to brother) or patrilineal (father to son) succession was to be preferred.[7]

- Moroccan war of succession (1465–1471), after the killing of Abd al-Haqq II of the Marinid Sultanate during the 1465 Moroccan revolution. The Marinid dynasty fell; the Idrisid Mohammed ibn Ali Amrani-Joutey and the Wattasid Abu Abd Allah al-Sheikh Muhammad ibn Yahya fought each other to found a new dynasty over Morocco.

- Ethiopian war of succession (1494–1495), after the death of emperor Eskender of the Ethiopian Empire (Solomonic dynasty)[8]

A diachronic map of various prominent pre-colonial African civilisations

- Adalite war of succession (1517–1527), after the death of sultan Mahfuz of the Adal Sultanate[9]

- Kongolese war of succession (1543–1545), after the death of mwenekongo Afonso I of Kongo[10]

- Bunyoro war of succession (mid-16th century), enthroning Winyi II over the Empire of Kitara[11] in 1570[12]

- Moroccan war of succession (1554), after the death of Sultan Ahmad of the Wattasid dynasty

- Moroccan war of succession (1574–1578), after the death of sultan Abdallah al-Ghalib of the Saadi dynasty[13]

- War of the Songhai succession (1582/3–1591), after the death of emperor Askia Daoud of the Songhai Empire.[14] The war between the two feuding fractions would not cease until the Saadian invasion of the Songhai Empire in 1591.[14]

- Moroccan War of Succession (1603–1627)[15]

- Kongo Civil War (1665–1709), after the death of mwenekongo António I of Kongo in the Battle of Mbwila[16]

- Revolutions of Tunis or the Muradid War of Succession (1675–1705), after the death of bey Murad II of Tunis

- Yatengan war of succession (1754–1757), after the death of Naaba ("king") Piiyo of Yatenga (modern Burkina Faso) between his brother Naaba Kango and his cousin Naaba Wobgho. Soon after Kango's ascension to the throne, Wobgho forced him into exile, but in 1757 Kango returned with Barbara troops with flintlocks (the first recorded use of firearms in Yatenga), and won the war.[17]

- Several Bunyoro wars of succession in the Empire of Kitara in the 17th and 18th century, almost always coinciding with rebellions in its tributary states[18]

- Tripolitanian civil war (1790–1795), after the assassination of bey Hasan of Tripoli. It involved a war of succession between leading members of the Karamanli dynasty, an intervention by Ottoman officer Ali Burghul who claimed to be acting on the sultan's orders and controlled Tripoli for 17 months, and an intervention by the bey of Tunis Hammuda ibn Ali to restore the Karamanlis to power.

- Lozi war of succession (c. late 1820s–1830s[19]), after the death of litunga Mulambwa Santulu of Barotseland between his sons Silumelume and Mubukwanu.[19] The two brothers fought with each other over the succession,[20] and Silumelume initially gained power and started to rule, but was then assassinated (perhaps on the orders of Mubukwanu), and then Mubukwanu began his reign. The Lozi were 'seriously weaked by [the] succession dispute', and then defeated by the Makololo invasion led by Sebetwane.[21]

- Zulu war of succession (1839–1840), between the brothers Dingane and Mpande after the Battle of Blood River[22]

- Burundian war of succession (c. 1850–1900), after the death of mwami Ntare Rugamba of the Kingdom of Burundi. Great controversy surrounds the parentage and accession of Mwezi Gisabo to the kingship (ubwami), as his older brother Twarereye had been their father's designated heir. The ensuing fratricidal war ultimately led to Twarereye's death in the Battle of Nkoondo (c. 1860) near the traditional capital of Muramvya. Dynastic feuds and challenges to Mwezi's kingship by his other brothers would continue for decades thereafter, and by 1900 Mwezi had only effective control over half his kingdom's territory.[23][24]

- Bunyoro war of succession (c. 1851), enthroning Kamurasi over the Empire of Kitara[12]

- Second Zulu Civil War (1856), during the late reign of king Mpande of the Zulu Kingdom between his sons Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi (Mpande's favourite and implied successor). As king Mpande was still alive, Cetshwayo's actions could be labelled a princely rebellion, but the literature often refers to the conflict as a "war of succession".[25][26][27]

- Gaza war of succession[28] (1858–1862[29][30]) between brothers Mawewe and Mzila[29] after the death of their father, king Soshangane of the Gaza Empire[31][30]

- Makololo war of succession (1863–1864), after the death of morêna Sekeletu of Barotseland, between Mamili/Mamile and Mbololo/Mpololo (Sekeletu's uncle, Sebetwane's brother).[32] It resulted in the extinction of the Makololo dynasty of Sebetwane in Barotseland, and led to the enthronement of Sipopa Lutangu (Mubukwanu's son, Mulambwa's grandson).[33] Conventional historiography regards the accession of Sipopa as "the 'Restoration' of the Lozi monarchy and the start of the 'Second Kingdom'",[34] but Flint (2005) argued that the Lozi and Makololo peoples were ethnolinguistically close and had 'effectively merged' in the decades following the accession of Sebetwane, demonstrated by the fact that both groups spoke the 'Sikololo' or 'Silozi' language by 1864.[35] Sipopa was 'on good terms with the Makololo hierarchy' and married Sebetwane's daughter Mamochisane upon his accession.[36]

- Ndebele war of succession (1868), after the death of king Mzilikazi of the Northern Ndebele kingdom of Mthwakazi, won by Lobengula[37]

- Ethiopian war of succession (1868–1872), after the suicide of emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia following his defeat in the British expedition to Abyssinia

- Bunyoro war of succession (1869), after the death of mukama Kamurasi, enthroning Kabalega over the Empire of Kitara[12]

- Anglo-Zanzibar War (27 August 1896), after the death of sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini of Zanzibar from the House of Busaid. His cousin Khalid bin Barghash of Zanzibar attempted to accede to the throne, but without approval of the British, who favoured a different cousin of Hamad: Hamoud bin Mohammed of Zanzibar. The British bombardment of Khalid's palace compelled him to surrender after about 40 minutes and abdicate in favour of Hamoud, marking the shortest war in recorded history.

- Ethiopian coup d'état of 1928 and Gugsa Wale's rebellion (1930), about the (future) succession of empress Zewditu of the Ethiopian Empire by Haile Selassie

Asia

- Central Asia

- East Asia

- North Asia

- Persia & Afghanistan

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- West Asia

Ancient Asia

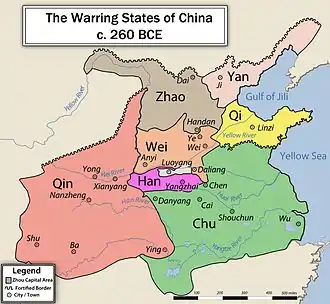

The Warring States, each claiming kingship and seeking to unite China under their banner.

- (historicity contested) Kurukshetra War, also called the Mahabharata or Bharata War (dating heavily disputed, ranging from 5561 to around 950 BCE), between the Pandava and Kaurava branches of the ruling Lunar dynasty over the throne at Hastinapura.[38] It is disputed whether this event actually occurred as narrated in the Mahabharata.

- Rebellion of the Three Guards (c. 1042–1039 BCE), after the death of King Wu of Zhou[39]

- (historicity contested) War of David against Ish-bosheth (c. 1007–1005 BCE), after the death of king Saul of the united Kingdom of Israel. It is disputed whether this event actually occurred as narrated in the Hebrew Bible. It allegedly began as a war of secession, namely of Judah (David) from Israel (Ish-bosheth), but eventually the conflict was about the succession of Saul in both Israel and Judah

- Neo-Assyrian war of succession (826–820 BCE), in anticipation of the death of king Shalmaneser III of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (died 824 BCE) between his sons Assur-danin-pal and Shamshi-Adad[40]

- Jin wars of succession (8th century–376 BCE), a series of wars over control of the Chinese feudal state of Jin (part of the increasingly powerless Zhou Dynasty)

- Jin–Quwo wars (739–678 BCE), dynastic struggles between two branches of Jin's ruling house[41]

- Partition of Jin (c. 481–403 BCE), a series of wars between rival noble families of Jin, who eventually sought to divide the state's territory amongst themselves at the expense of Jin's ruling house. The state was definitively carved up between the successor states of Zhao, Wei and Han in 376 BCE.

- Zheng war of succession (701–680 BCE), after the death of Duke Zhuang of Zheng[42][43]

- War of Qi's succession (643–642 BCE), after the death of Duke Huan of Qi

- (debated) Accession of Darius the Great (522 BCE), after the death of Cambyses II of the Achaemenid Empire. Scholars debate how Cambyses II died, and how Darius the Great got into power, because the sources (such as the Behistun Inscription, Ctesias and Herodotus) contradict each other and are unreliable in certain places. What is clear is that there was some sort of power struggle following the death of Cambyses, possibly involving the assassinations of Cambyses and Bardiya, and coups d'état, that eventually Darius acceded to the throne, and that he had to quell multiple rebellions against his new reign.[44]

- Persian war of succession (404–401 BCE) ending with the Battle of Cunaxa, after the death of Darius II of the Achaemenid Empire

- Warring States period (c. 403–221 BCE), a series of dynastic interstate and intrastate wars during the Eastern Zhou dynasty of China over succession and territory

- War of the Wei succession (370–367 BCE), after the death of Marquess Wu of Wei. Featuring the Battle of the Turbid Swamp.

- Qin's wars of unification (230–221 BCE), to enforce Qin's claim to succeeding the Zhou dynasty (which during the Western Zhou period ruled all the Chinese states), that Qin had ended in 256 BCE

- Wars of the Diadochi or Wars of Alexander's Successors (323–277 BCE), after the death of king Alexander the Great of Macedon[3]

- Maurya war of succession (272–268 BCE), after the death of emperor Bindusara of the Mauryan Empire; his son Ashoka the Great defeated and killed his brothers, including crown prince Susima[45]

- Bithynian war of succession (255–254 BCE), after the death of king Nicomedes I of Bithynia

- Chu–Han Contention (206–202 BCE), after the surrender and death of emperor Ziying of the Qin dynasty; the rival rebel leaders Liu Bang and Xiang Yu sought to set up their own new dynasties

- Lü Clan Disturbance (180 BCE), after the death of Empress Lü of the Han dynasty

The Seleucid Dynastic Wars ravaged the once great Seleucid Empire, and contributed to its fall.

- Seleucid Dynastic Wars (157–63 BCE), a series of wars of succession that were fought between competing branches of the Seleucid Royal household for control of the Seleucid Empire

- (uncertain) Bactrian war of succession (c. 145–130 BCE), after the assassination of king Eucratides I of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, between his sons Eucratides II, Heliocles I and Plato

- Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BCE), after the death of king Nicomedes IV of Bithynia between the Roman Republic and the Kingdom of Pontus

- Hasmonean Civil War (67–63 BCE), after the death of queen Salome Alexandra of Hasmonean Judea between her sons Aristobulus II and Hyrcanus II[3]: 93–94

- Parthian war of succession (57–54 BCE), between Mithridates IV and his brother Orodes II after killing their father, king Phraates III

- The Roman invasion of Parthia in 54 BCE, ending catastrophically at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, was partially motivated by or justified as supporting Mithridates' claim to the Parthian throne[46]

- Red Eyebrows and Lulin Rebellions (17–23 CE), revolts against Xin dynasty emperor Wang Mang to restore the Han dynasty; both rebel armies had their own candidates, however

- Han civil war (23–36), Liu Xiu's campaigns against pretenders and regional warlords who opposed the rule of the Gengshi Emperor (23–25) and his own rule (since 25)[47]

- Second Red Eyebrows Rebellion (23–27), after the death of Wang Mang, against the Gengshi Emperor, the Lulin rebel candidate to succeed Wang Mang

- War of the Armenian Succession (54–66), caused by the death of Roman emperor Claudius, after which the rival pretender Tiridates was installed by king Vologases I of Parthia, unacceptable to new emperor Nero[48]

- Parthian wars of succession between Vologases III, Osroes I, Parthamaspates, Mithridates V and Vologases IV (105–147), after the death of king Pacorus II of Parthia

- Trajan's Parthian campaign (115–117), the intervention of the Roman emperor Trajan in favour of Parthamaspates[48]

- Three Kingdoms Period (184–280), after the death of emperor Ling of Han[lower-alpha 1]

- Yuan clan war of succession (202–205), after the death of clan leader Yuan Shao[49]

- Dynastic struggle between Vologases VI and Artabanus IV (213–222), after the death of their father Vologases V of Parthia

- Parthian war of Caracalla (216–217), Roman intervention in the Parthian dynastic struggle against Artabanus IV

- War of the Eight Princes (291–306), after the death of emperor Sima Yan of the Chinese Jin dynasty

- (historicity contested) A war of succession in the Gupta Empire after the death of emperor Kumaragupta I (c. 455), out of which Skandagupta emerged victorious. Historical sources do not make clear whether the events described constituted a war of succession, and whether it even took place as narrated.[50]

- Sasanian war of succession (457–459) between Hormizd III and Peroz I after the death of their father, shahanshah Yazdegerd II of the Sasanian Empire

- War of the Uncles and Nephews (465–c.495) after the death of emperor Qianfei of the Liu Song dynasty[51]

- Prince Hoshikawa Rebellion (479–480), after the death of emperor Yuryaku of Japan

Medieval Asia

- Wei civil war (530–550), after the assassination of would-be usurper Erzhu Rong by emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei, splitting the state into Western Wei (Yuwen clan) and Eastern Wei (Gao clan)

- Göktürk civil war or Turkic interregnum (581–587), after the death of Gökturk khagan Taspar Qaghan of the First Turkic Khaganate[52]

- Yamato war of succession (585–587), after the death of emperor Bidatsu of Yamato (Japan). Also the final phase of the religion-based Soga–Mononobe conflict (552–587) between the pro-Shinto Mononobe clan and the pro-Buddhist Soga clan.[53]

- Sasanian civil war of 589-591, about the deposition, execution and succession of shahanshah Hormizd IV of the Sasanian Empire

- Sui war of succession (604), after the death of Emperor Wen of the Sui dynasty[54]

- Chalukya war of succession (c. 609), after the death of king Mangalesha of the Chalukya dynasty[55]

- Transition from Sui to Tang (613–628): with several rebellions against his rule going on, Emperor Yang of Sui was assassinated in 618 by rebel leader Yuwen Huaji, who put Emperor Yang's nephew Yang Hao on the throne as puppet emperor, while rebel leader Li Yuan, who had previously made Emperor Yang's grandson Yang You his puppet emperor, forced the latter to abdicate and proclaimed himself emperor, as several other rebel leaders had also done.

- Sasanian civil war of 628–632 or Sasanian Interregnum, after the execution of shahanshah Khosrow II of the Sasanian Empire

Ali and Aisha at the Battle of the Camel. Originally a political conflict on the Succession to Muhammad, the First Fitna became the basis of the religious split between Sunni Islam and Shia Islam.

- The historical Fitnas in Islam:

- First Fitna (656–661), after the assassination of caliph Uthman of the Rashidun Caliphate between the Umayyads and Ali's followers (Shiites)

- Second Fitna (680–692; in strict sense 683–685), after the death of caliph Mu'awiya I of the Umayyad Caliphate between Umayyads, Zubayrids and Alids (Shiites)

- Third Fitna (744–750/752): a series of civil wars within and rebellions against the Umayyad Caliphate, starting with the assassination of caliph Al-Walid II, and ending with the Abbasid Revolution

- Fourth Fitna (811–813): under the reign of the caliph Muhammad Al-Amin of the Abbasid Caliphate

- Fifth Fitna (865–866); after the death of Al-Muntasir of the Abbasid Caliphate.

- War of the Goguryeo succession (666–668), after the death of military dictator Yeon Gaesomun of Goguryeo, see Goguryeo–Tang War (645–668)

- Jinshin War (672), after the death of emperor Tenji of Yamato (Japan)

- Twenty Years' Anarchy (695–717), after the deposition of emperor Justinian II of the Byzantine Empire

- Abbasid war of succession (754), after the death of the first Abbasid caliph As-Saffah. Decisive battle at Nisibis in November 754.

- Rashtrakuta war of succession (c. 793), after the death of emperor Dhruva Dharavarsha of the Rashtrakuta dynasty[56]

- Era of Fragmentation (842–1253), after the assassination of emperor Langdarma of the Tibetan Empire

- Anarchy at Samarra (861–870), after the assassination of caliph Al-Mutawakkil of the Abbasid Caliphate

- Abbasid civil war or Fifth Fitna (865–866), after the death of caliph Al-Muntasir of the Abbasid Caliphate[57]

- Later Three Kingdoms of Korea (892–936), began when two rebel leaders, claiming to be heirs of the former kings of Baekje and Goguryeo, revolted against the reign of queen Jinseong of Silla

- Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–979), after the deposition (and 908) murder of emperor Ai of Tang, ending the Tang dynasty. Subsequent decades saw widespread warfare between various warlords claiming to have succeeded or restored the Tang dynasty.

- Pratihara war of succession (c. 910–913), after the death of king Mahendrapala I of the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty[58]

- Covenant Crossing (947) after the death of Emperor Taizong of Liao (Liao dynasty)

- Buyid war of succession (949–979), after the death of emir Imad al-Dawla of the Buyid dynasty[59][60]

- Anarchy of the 12 Warlords (966–968), after the death of king Ngô Quyền of Vietnam

- Samanid war of succession (961–962), after the death of emir Abd al-Malik I of the Samanid Empire between his brother Mansur (supported by Fa'iq) and his son Nasr (supported by Alp-Tegin). Alp-Tegin lost, but managed to establish an autonomous governorship in Ghazni, where his son-in-law Sabuktigin founded the Ghaznavid dynasty in 977.[61]: 8:44

- Buyid war of succession (983–998), after the death of emir 'Adud al-Dawla of the Buyid dynasty[59]

- Afghan War of Succession (997–998),[62] after the death of emir Sabuktigin of the Ghaznavids

- Khmer war of succession (c. 1001–1006/11), after the death of king Jayavarman V of the Khmer Empire[63] between Udayadityavarman I (r. 1001–1002), Suryavarman I (r. 1002/6–1050) and Jayavirahvarman (r. 1002–1010/11)

- Afghan war of succession (1030), after the death of sultan Mahmud of Ghazni

- Afghan War of Succession (1041), after the death of sultan Mas'ud I of Ghazni[62]

- Seljuk war of succession (1063), after the death of sultan Tughril, founder of the Seljuk Empire

- Seljuk war of succession (1072–1073), after the death of sultan Alp Arslan of the Seljuk Empire. Decided at the Battle of Kerj Abu Dulaf.

- Seljuk War of Succession (1092–1105), after the death of sultan Malik Shah I of the Seljuk Empire[64]

- Seljuk war of succession in Iraq (1131–1134?), after the death of Mahmud II, the Seljuk sultan of Baghdad

- Seljuk war of succession in Iraq and Persia (1152–1159), after the death of Ghiyath ad-Din Mas'ud, the Seljuk sultan of Baghdad and Hamadan

- Hōgen Rebellion (1156), Heiji Rebellion (1160) and Genpei War (1180–1185), after the death of emperor Konoe of Japan, between clans over control of the imperial family

- Pandyan Civil War (1169–1177): king Parakrama Pandyan I and his son Vira Pandyan III against Kulasekhara Pandya of Chola

- War of the Antiochene Succession (1201–1219), after the death of prince Bohemond III of Antioch

- War of the Lombards (1228–1243), after the death of queen Isabella II of Jerusalem and Cyprus

- Ayyubid war of succession (1238–1249), after the death of sultan Al-Kamil of the Ayyubid dynasty

- Toluid Civil War (1260–1264), after the death of great khan Möngke Khan of the Mongol Empire between Ariq Böke and Kublai Khan[65]: 5:23–9:41

- Kaidu–Kublai war (1268–1301/4), continuation of the Toluid Civil War caused by Kaidu's refusal to recognise Kublai Khan as the new great khan[66]

- Chagatai wars of succession (1307–1331), after the death of khan Duwa of the Chagatai Khanate[67][65]: 32:47–33:39

- Pandya Fratricidal War (c. 1310–?), after the death of king Maravarman Kulasekara Pandyan I of the Pandya dynasty[68][69]

- Golden Horde war of succession (1312–1320?), after the death of khan Toqta of the Golden Horde

- War of the Two Capitals (1328–1332), after the death of emperor Yesün Temür of the Yuan dynasty[65]: 44:37–46:20

- Disintegration of the Ilkhanate (1335–1353), after the death of il-khan Abu Sa'id of the Ilkhanate[65]: 18:26–29:04

- Chagatai wars of succession (1334–1347), after the deposition and killing of khan Tarmashirin of the Chagatai Khanate. As a result, the Chagatai Khanate effectively split into Transoxania in the west, and Moghulistan in the east.[65]: 33:48–35:22

- Nanboku-chō period or Japanese War of Succession[70] (1336–1392), after the ousting and death of emperor Go-Daigo of Japan

- Trapezuntine Civil War (1340–1349), after the death of emperor Basil of Trebizond

- Tughlugh Timur's invasions of Transoxania (1360–1361), after the assassination of Amir Qazaghan of Transoxania[65]: 35:39–35:56

- Ottoman war of succession (1362), after the death of sultan Orhan between şehzade (prince) Murad I, şehzade Ibrahim Bey (1316–1362; governor of Eskişehir) and şehzade Halil.[71]: 7:02–7:55 Murad won and executed his half-brothers Ibrahim and Halil, the first recorded instance of Ottoman royal fratricide.[71]: 7:02–7:55

- Forty Years' War (1368–1408) after the death of king Thado Minbya of Ava; the war raged within and between the Burmese kingdoms of Ava and Pegu as the successors of the Pagan Kingdom[72]

- Tran war of succession (1369–1390), after the death of king Trần Dụ Tông of the Trần dynasty[73]

- Delhi war of succession (1394–1397), after the death of sultan Ala ud-din Sikandar Shah of the Tughlaq dynasty (Delhi Sultanate)[74][75]

- Strife of Princes (1398–1400), after king Taejo of Joseon appointed his eighth son as his successor instead of his disgruntled fifth, who rebelled when he learnt that his half-brother was conspiring to kill him (see also History of the Joseon dynasty § Early strife)[76]

- Jingnan Rebellion (1399–1402), after the death of the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming dynasty

- Regreg War (1404–1406), resulting from succession disputes after the death (1389) of king Hayam Wuruk of the Majapahit Empire

- Timurid wars of succession (1405–1507):

- First Timurid war of succession (1405–1409/11), after the death of amir Timur of the Timurid Empire[77]

- Second Timurid war of succession (1447–1459), after the death of sultan Shah Rukh of the Timurid Empire[77]

- Third Timurid war of succession (1469–1507), after the death of sultan Abu Sa'id Mirza of the Timurid Empire[77]

- Sekandar–Zain al-'Abidin war (1412–1415): according to the Ming Shilu, Sekandar was the younger brother of the former king, rebelled and plotted to kill the current king Zain al-'Abidin to claim the throne of the Samudera Pasai Sultanate; however, the Ming dynasty had recognised the latter as the legitimate ruler, and during the fourth treasure voyage of admiral Zheng He, the Chinese intervened and defeated Sekandar.[78]

- Ottoman war of succession (1421–1422/30), after the death of sultan Mehmed I of the Ottoman Empire between his younger brother Mustafa Çelebi, his oldest son Murad II, and his second-oldest son Küçük Mustafa[79]

- During the Siege of Thessalonica (1422–1430), a Turkish pretender (known as "Pseudo-Mustafa") claiming to be Mustafa Çelebi was supported by the Byzantines

- Gaoxu rebellion (1425), after the death of the Hongxi Emperor of the Chinese Ming dynasty

- Kakitsu Chaos (July–September 1441), after the assassination of shogun Ashikaga Yoshinori of Japan. Not to be confused with the Kakitsu uprising that happened simultaneously.

- Shiro Furi Rebellion (1453), after the death of king Shō Kinpuku of the Ryukyu Kingdom, between the king's son Shiro (志魯, also Shiru, Chinese Shilu) and his younger brother Furi (布里, also Buri, Chinese Buli).

- Sengoku period (c. 1467–1601) in Japan

- Ōnin War (1467–1477), after the 1464 abdication of Emperor Go-Hanazono of Japan in favour of Emperor Go-Tsuchimikado,[80] as well as the imminent succession of shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa of Japan

- Aq Qoyunlu war(s) of succession (1470s–1501), after the death of shahanshah Uzun Hasan of the Aq Qoyunlu state[81][82]

Early Modern Asia

War of 1657–61. Mughal emperors were often overthrown by their sons, who then warred each other to the death.[83]

Mir Jafar defected to the British during the Battle of Plassey, being made the new nawab of Bengal as a reward.

- Khandesh war of succession (1508–1509), after the death of sultan Ghazni Khan of the Farooqi dynasty (Sultanate of Khandesh)[84]

- Trần Cao rebellion (1516–1521), after the deposition of emperor Lê Tương Dực of the Lê dynasty of Đại Việt by the spring 1516 military coup

- Northern Yuan war of succession (1517–15??), after the death of khagan Dayan Khan of the Northern Yuan dynasty[85]

- Negara Daha war of succession (c. 1520), between Suriansyah of Banjar (alias Prince Samudera) and his uncle Pangeran Tumenggung[86]

- Crisis of the Sixteenth Century (1521–1597), after the overthrow and murder of king Vijayabahu VI of Kotte during the Vijayabā Kollaya. The three sons of his first wife had conspired to kill him to prevent his designated heir, their stepbrother from his second wife, to ascend to the throne. Although they managed to kill their father, they soon began fighting each other over the division of the kingdom of Kotte in three parts, while the Kingdom of Kandy seized the opportunity to reassert its independence. The Portuguese started intervening in the war in the 1540s for commercial concessions, and finally inherited reunited Kotte (without Kandy) in 1597.[87]

- Gujarati war of succession (1526–1527), after the death of sultan Muzaffar Shah II of the Gujarat Sultanate[88]

- Lê–Mạc War (1527/33–1592), after the deposition and execution of puppet-emperor Lê Cung Hoàng by general Mạc Đăng Dung, who proclaimed himself the emperor of his own new Mạc dynasty. Lê dynasty loyalists revolted, and in 1533 enthroned Lê Trang Tông.

- Hanakura Rebellion (1536), after the death of daimyo Imagawa Ujiteru of the Imagawa clan (controlling the Suruga Province of Japan)

- Mughal war of succession (1540–1552), between the brothers Humayun and Kamran Mirza about the succession of their already 10 years earlier deceased father, emperor Babur of the Mughal Empire[89]

- Burmese–Siamese War (1547–1549), after the death of king Chairachathirat of Ayutthaya,[90] followed by a succession crisis involving two coups and royal assassinations of kings Yotfa and Worawongsathirat

- Safavid war of succession (1576–1578), after the death of shah Tahmasp I of Persia[91]

- Mughal war of succession (1601–1605), in advance of the death of emperor Akbar of the Mughal Empire[92]

- Siamese war of succession (1610–1611), after the death (murder?) of king Ekathotsarot of the Ayutthaya Kingdom[93]

- Karnataka war of succession (1614–1617), after the death of emperor Venkatapati Raya of the Vijayanagara Empire[94]

- Jaffna war of succession (1617–1621; last phase of the Portuguese conquest of the Jaffna kingdom), after the death of king Ethirimana Cinkam (Parasasekaran VIII) of the Jaffna Kingdom

- Mughal war of succession (1627–1628), after the death of emperor Nuruddin Salim Jahangir of the Mughal Empire

- Siamese war of succession (1628–1629), after the death of king Songtham of the Ayutthaya Kingdom[93]

- Mataram war of succession (1645–1648), after the sudden death of Sultan Agung of Mataram. To prevent succession disputes from challenging his legitimacy, Agung's son Amangkurat I (crowned with heavy military security in 1646) launched many pre-emptive strikes (assassinations, massacres and battles) to eliminate potential rivals to the throne, including many noblemen and military leaders such as Tumenggung Wiraguna and his whole family (1647). This led his younger brother Prince Alit (patron of the Wiraguna family) to attempt to overthrow him by attacking the royal palace with the support of Islamic clerics (ulema) and devout Muslims in 1648, but they were defeated and Alit was slain in battle. Two days later, Amangkurat I committed a Massacre of the ulema and their families (about 5,000–6,000 people) to secure his reign.[95]

- Mughal war of succession (1657–1661),[96] after grave illness of emperor Shah Jahan of the Mughal Empire.[83] Scholars disagree about whether to label this conflict a 'war of succession' or a '(princely) rebellion'.[lower-alpha 2]

- Brunei Civil War (1660–1673), after the killing of sultan Muhammad Ali of the Bruneian Sultanate by Abdul Hakkul Mubin, who seized the throne

- Tungning war of succession (1662), after the death of king Koxinga of the Kingdom of Tungning

- During the Trunajaya rebellion (1674–1681), sultan Amangkurat I of Mataram died in 1677, causing a war of succession between his sons Rahmat (Amangkurat II) and Puger (Pakubuwono I)

- Laotian wars of succession[98] (1694–1707/1713), after the death of king Sourigna Vongsa of Lan Xang

- The Javanese Wars of Succession (1703–1755), between local pretenders and candidates of the Dutch East India Company for the Sultanate of Mataram on Java

- First Javanese War of Succession (1703–1708), after the death of sultan Amangkurat II of Mataram between his son Amangkurat III of Mataram and his brother Puger (Pakubuwono I)

- Second Javanese War of Succession (1719–1722)

- Third Javanese War of Succession (1749–1755)

- Sikkimese War of Succession (c. 1699–1708), after the death of chogyal Tensung Namgyal of the Kingdom of Sikkim[99]

- Mughal war of succession (1707–1709), after the death of emperor Aurangzeb of the Mughal Empire[100][101][102]

- Mughal war of succession (1712–1720), after the death of emperor Bahadur Shah I of the Mughal Empire[103]

- Marava War of Succession (1720–1729), after the death of raja Raghunatha Kilavan of the Ramnad estate

- Persian or Iranian Wars of Succession (1725–1796)[104]

- Safavid war of succession (1725–1729), after a Hotak invasion and the imprisonment of shah Sultan Husayn of Safavid Persia

- Afsharid war of succession (1747–1757), after the death of shah Nadir Shah of Afsharid Persia

- Zand war of succession (1779–1796), after the death of Karim Khan of Zand Persia

- Carnatic Wars (1744–1763), territorial and succession wars between several local, nominally independent princes in the Carnatic, in which the British East India Company and French East India Company mingled

- First Carnatic War (1744–1748), part of the War of the Austrian Succession between, amongst others, France on the one hand, and Britain on the other

- Second Carnatic War (1749–1754), about the succession of both the nizam of Hyderabad and the nawab of Arcot

- Third Carnatic War (nl) (1756–1763), after the death of nawab Alivardi Khan of Bengal; part of the global Seven Years' War between amongst others France on the one hand and Britain on the other

- Maratha war of succession (1749–1752), after the death of maharaja Shahu I of the Maratha Empire[105]

- Burmese war of succession (1760–1762), after the death of king Alaungpaya of the Konbaung dynasty[106]

- War of the Sumbawan Succession (1761/2–1765), after the deposition of sultana I Sugiratu Karaeng Bontoparang (alias Sultanah Siti Aisyah, the wife of sultan Qahar-al-Din, who died in 1758) of the Sumbawa Sultanate. The war raged between the newly council-elected sultan Hasan al-Din (alias Hasanuddin, the Datu of Jarewe) and the council chief the Nene Rangan on the one hand (later supported by Balinese troops from Lombok), and Muhammad Jalaluddin Shah II (the Datu of Taliwang) and Mille Ropia on the other hand (later supported by Dutch East India Company (VOC) forces). The VOC defeated and captured Hasan al-Din and installed Jalaluddin as the new sultan in February 1764, but upon gathering more information decided that Hasan al-Din was the rightful sultan after all, and reinstalled him.[107]

- Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775–1819): wars of succession between peshwas, in which the British intervened, and conquered the Maratha Empire

- First Anglo-Maratha War (1775–1782), after the death of peshwa Madhavrao I; pretender Raghunath Rao invoked British help, but lost

- Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805), pretender Baji Rao II, son van Raghunath Rao, triumphed with British help and became peshwa, but had to surrender much power and territory to the British

- Third Anglo-Maratha War, also Pindari War (1816–1819), peshwa Baji Rao II revolted against the British in vain; the Maratha Empire was annexed

Dutch cavalry charge during the 1859 Bone Expedition on Sulawesi.

- Banjarmasin war of succession (1785–1787), after the death of sultan Tahhmid Illah I of the Sultanate of Banjar(masin). The Dutch East India Company (VOC) intervened in 1786 in favour of Pangeran Nat(t)a (known by many other names), and upon victory he had to cede part of his territory to the VOC.[108][109]

- Kurnool war of succession (1792–?), after the death of nawab Ranmust Khan of Kurnool between his sons Azim Khan (supported by the Nizam of Hyderabad) and Alif Khan (supported by the Sultan of Mysore)[110]

Modern Asia

- Afghan Wars of Succession (1793–1834?), after the death of emir Timur Shah Durrani of Afghanistan[111]

- First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842), British–Indian invasion of Afghanistan under the pretext of restoring the deposed emir Shah Shujah Durrani[112]

- Pahang Civil War (1857–1863), after the death of raja Tun Ali of Pahang

- Later Afghan War of Succession (1865–1870), after the death of emir Dost Mohammed Khan of Afghanistan

- The Dutch East Indies Army's 1859–1860 Bone Expeditions dealt with a war of succession in the Sulawesi kingdom of Bone

- In the Second Bone War (1858–1860), the Dutch supported pretender Ahmad Sinkkaru' Rukka against queen Besse Arung Kajuara after the death of her husband, king Aru Pugi[113][114]

- The Banjarmasin War (1859–1863), after the death of sultan Adam. The Dutch supported pretender Tamjid Illah against pretender Hidayat Ullah; the latter surrendered in 1862.[109]

- Third and Fourth Larut Wars (1871–1874), after the death of Sultan Ali (r. 1865–1871) of Perak

- Nauruan Civil War (1878–1888), after the crown chief was fatally shot during a heated discussion, shattering the existing federation of tribes and triggering a war between two tribal factions

Europe

- British Islands

- Scandinavia, Baltics & Eastern Europe

- Low Countries

- Central Europe (HRE)

- France & Italy

- Spain & Portugal

- Southeastern Europe

Ancient Europe

- Six-year Macedonian interregnum (399–393 BCE), after the death of king Archelaus I, between Crateuas, Orestes, Aeropus II, Amyntas II "the Little", Derdas II, Archelaus II, and Pausanias[115][116]: 18:56

- Macedonian war of succession (393–392 BCE), after the death of king Pausanias of Macedon, between Amyntas III and Argaeus II[117]

- Macedonian war of succession (369–368 BCE), after the death of king Amyntas III of Macedon, between Ptolemy of Aloros and Alexander II of Macedon[118]: 2:25

- Macedonian war of succession (360–359 BCE), after the death of king Perdiccas III of Macedon, between Philip II (who deposed Amyntas IV), Argeus (supported by Athens), Pausanias (supported by Thrace) and Archelaus (supported by the Chalcidian League)[119][118]: 6:01

- Thracian war of succession (c. 352–347 BCE), after the death of co-king Berisades of Thrace (Odrysian kingdom), between Cetriporis and his brothers against their uncle Cersobleptes

- Wars of the Diadochi or Wars of Alexander's Successors (323–277 BCE), after the death of king Alexander the Great of Macedon[3]

- First War of the Diadochi (322–320 BCE), after regent Perdiccas tried to marry Alexander the Great's sister Cleopatra of Macedon and thus claim the throne

- Second War of the Diadochi (318–315 BCE), after the death of regent Antipater, whose succession was disputed between Polyperchon (Antipater's appointed successor) and Cassander (Antipater's son)

- Epirote war of succession (316–297 BCE), after the deposition of king Aeacides of Epirus during his intervention in the Second War of the Diadochi until the second enthronement of his son Pyrrhus of Epirus and the death of usurper Neoptolemus II of Epirus

- Third War of the Diadochi (314–311 BCE), after the diadochs conspired against Antigonus I Monophthalmus and Polyperchon

- Fourth War of the Diadochi (308/6–301 BCE), resumption of the Third. During this war, regent Antigonus and his son Demetrius both proclaimed themselves king, followed by Ptolemy, Seleucus, Lysimachus, and eventually Cassander.

- Struggle over Macedon (298–285 BCE), after the death of king Cassander of Macedon

- Struggle of Lysimachus and Seleucus (285–281 BCE), after jointly defeating Demetrius and his son Antigonus Gonatas

- Bosporan Civil War (c. 310–309 BCE), after the death of archon Paerisades I of the Bosporan Kingdom[120][121][122]

- Pergamene–Bosporan war (c. 47–45 BCE), after the death of king Pharnaces II of Pontus and the Bosporus, between Pharnaces' daughter Dynamis (and her husband Asander) and Pharnaces' brother Mithridates of Pergamon (supported by the Roman Republic)

- Pontic–Bosporan war (c. 17–16 BCE), after the death of king Asander of the Bosporus, between usurper Scribonius (who married queen Dynamis) and the Roman client king Polemon I of Pontus (supported by general Agrippa of the Roman Empire)

- Roman–Bosporan War (c. 45–49 CE), after the deposition of king Mithridates of the Bosporan Kingdom by Roman emperor Claudius and the enthronement of Mithridates' brother Cotys I; Mithridates soon challenged his deposition and fruitlessly warred against Cotys and the Roman Empire[120][123][124]

- Boudica's Revolt (60 or 61), after the death of king Prasutagus of the Iceni tribe. The Romans failed to respect Prasutagus's will that emperor Claudius and his daughters would share his inheritance; instead, Roman soldiers occupied and pillaged the Iceni territory and raped Prasutagus's daughters, causing his widow queen Boudica to rise in rebellion.[125]

- Year of the Four Emperors (68–69), a rebellion in the Roman Empire that became a war of succession after the suicide of emperor Nero

- Year of the Five Emperors (193), the beginning of a war of succession that lasted until 197, after the assassination of the Roman emperor Commodus

- Crisis of the Third Century (235–284), especially the Year of the Six Emperors (238), a series of wars between barracks emperors after the assassination of Severus Alexander

- Civil wars of the Tetrarchy (306–324), after the death of Augustus (senior Roman emperor) Constantius I Chlorus

- War of Magnentius (350–353), after the assassination of Roman co-emperor Constans I

- War between Western Roman emperor Eugenius and Eastern Roman emperor Theodosius I (392–394), after the death of emperor Valentinian II, resulting in the Battle of the Frigidus

- War of the Hunnic succession (453–454), after the death of Attila, ruler of the Huns

Early Medieval Europe

- Fredegund–Brunhilda wars or Merovingian throne struggle (568–613), after the assassination of queen Galswintha of Neustria (sister of Brunhilda of Austrasia, both daughters of Visigothic king Athanagild) by her husband king Chilperic I of Neustria and his mistress Fredegund, who then married. Brunhilda then persuaded her husband, king Sigebert I of Austrasia, to wage war on Fredegund and Chilperic to avenge her sister and restore the Visigothic royal family's position of power over Neustria.[126] Fredegund had Sigebert (575) and her own husband Chilperic (584) assassinated, ruling as her son Chlothar II's regent and warring against Austrasia until her death in 597. Chlothar II continued this war until he captured and executed Brunhilda (613), briefly reuniting the Frankish Empire.[127]

- Lombard war of succession (661–662), after the death of king Aripert I of the Kingdom of the Lombards

- Lombard war of succession (668–669), after the death of king Perctarit of the Kingdom of the Lombards

- Neustrian war of succession (673), after the death of king Chlothar III of Neustria. Mayor Ebroin enthroned puppet-king Theuderic III, but Neustrian aristocrats revolted and offered the crowns of Neustria and Burgundy to king Childeric II of Austrasia, who emerged victorious and briefly reunited the Frankish Empire.[128]

- Frankish war of succession (675–679), after the assassination of the Frankish king Childeric II and queen Bilichild (675); mayor Ebroin once again enthroned puppet-king Theuderic III, and emerged victorious in the Battle of Lucofao.[128]

- Twenty Years' Anarchy (695–717), after the deposition of emperor Justinian II of the Byzantine Empire

- Lombard war of succession (700–712), after the death of king Cunipert of the Kingdom of the Lombards

- Frankish Civil War (715–718) (nl), after the death of mayor of the palace Pepin of Herstal

- Siege of Laon (741), after the death of mayor of the palace Charles Martel

- Lombard war of succession (756–757), after the death of king Aistulf of the Kingdom of the Lombards

- Danish war of succession (812–814), after the death of king Hemming of Denmark

- (uncertain) Gwynedd war of succession (c. 816-825) between the two brothers Hywel ap Rhodri Molwynog and Cynan Dindaethwy ap Rhodri[129]: 4:22

- Carolingian wars of succession (830–842), a series of armed conflicts in the late Frankish Carolingian Empire about the (future) succession of emperor Louis the Pious[130]

- War of the Northumbrian succession (865–867), between king Osberht and king Ælla of Northumbria; their infighting was interrupted when the Great Heathen Army invaded, against which they vainly joined forces

- Carolingian war of succession (c. 887–890), after the deposition (November 887) and death (January 888) of emperor Charles the Fat. Contenders included Arnulf of Carinthia (who had deposed Charles, and became king of East Francia), Odo of France (crowned king of (West) Francia in February 888), Berengar I of Italy (possibly began reigning as king of Italy in December 887), Guy III of Spoleto (crowned king of Italy in 889), Louis the Blind (king of Provence since January 887), Rudolph I of Burgundy (elected king, ruled Upper Burgundy, fought with Arnulf over Lotharingia), and Ranulf II of Aquitaine (declared himself king and ruled in Aquitaine until 889/890).

- Serbian war of succession (892–897), after the death of prince Mutimir of Serbia[131]

- Svatopluk II rebellion (895–899?), after the death of duke Svatopluk I of Great Moravia

- Æthelwold's Revolt (899–902), after the death of king Alfred the Great of Wessex

- War of the Leonese succession (951–956), after the death of king Ramiro II of León[132]

- (historicity contested) Olga's Revenge on the Drevlians (945–947), after the Kyivan Rus' Drevlian vassals assassinated Igor of Kyiv. Initially, the Drevlian prince Mal offered to marry Igor's widow Olga of Kyiv and thus succeed him, but Olga appointed herself as regent over her young son Svyatoslav, made war on the Drevlians and destroyed their realm. The historicity of the events as described in the main document on the conflict, the Primary Chronicle, is contested, and the war is described as 'legendary' with a mix of fact and fiction.

- Gwynedd war of succession (950), after the death of king Hywel Dda of Gwynedd and Deheubarth[129]: 16:42

- Feud of the Svyatoslavychivi or Kyivan Rus' Dynastic War (c. 972–980), after the death of king Svyatoslav I of Kyiv[133]

- War of the Leonese succession (982–984), continuation of the last Leonese war of succession

- Stephen–Koppány war, also known as 'Koppány's rebellion' or contemporaneously 'the war between the Germans and the Hungarians' (997–998), after the death Géza, Grand Prince of the Hungarians. Stephen (pagan birth name: Vajk) was Géza's oldest son and claimed the throne by primogeniture; his army was described as 'the Germans'. Koppány was the brother of Géza's widow Sarolt and claimed the throne by agnatic seniority; his army was described as 'the Hungarians'. Later Christian sources emphasise Stephen's Christianity as an argument for his legitimacy, claim that Koppány was a pagan and that agnatic seniority was a 'pagan' custom as opposed to the 'Christian' custom of primogeniture, and that therefore Koppány 'rebelled' against the legitimate Christian king Stephen, but the reliability and impartiality of these sources is disputed.

High Medieval Europe

In 1066, William of Normandy managed to enforce his claim to the English throne.

- Bohemian war of succession (999–1012), after the death of duke Boleslaus II "the Pious" of Bohemia between his three sons Boleslaus III, Jaromír, and Oldřich.[134]

- German–Polish War (1003–1018), erupted due to clashing interventions of Polish duke Bolesław I the Brave and German king (from 1014 emperor) Henry II in the Bohemian war of succession.[135]

- German war of succession (January–October 1002), after the death of Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor.[136] See also 1002 German royal election.

- War of the Burgundian Succession (1002–1016), after the death of duke Henry I the Great of Burgundy

- Fitna of al-Andalus (1009–1031), after the deposition of caliph Hisham II of Córdoba

- Lower Lorrainian war of succession (1012–1018), after the death of Otto, Duke of Lower Lorraine[137]

- Kyivan succession crisis (1015–1019), also known as Feud of the Volodymyrovychi or Internecine war of Rus' (1015–1019), after the death of grand prince Volodymyr I Svyatoslavych "the Great" of Kyivan Rus'[138]

- Bolesław I's intervention in the Kievan succession crisis (1018), duke Bolesław I the Brave of Poland supported Sviatopolk the Accursed's claim against Yaroslav the Wise

- Cnut's conquest of England (1014–1016), after the death of Sweyn Forkbeard, King of the English

- Norwegian War of Succession[139] (1025/6–1035), after the departure of king Cnut the Great of Denmark to England. It started with the Battle of Helgeå;[139] it only became a war of succession when king Olaf II of Norway was deposed in 1028 and killed in the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030.

- Norman war of succession (1026), after the death of duke Richard II of Normandy between his sons Richard III and Robert I

- Norman war of succession (1035–1047), after the death of duke Robert I of Normandy. The Battle of Val-ès-Dunes is generally regarded as having secured the reign of William of Normandy[140][lower-alpha 3]

- Kalbid war of succession (1044–1061), after the deposition of the Kalbid emir Hasan as-Samsam of Sicily.[141] The Emirate of Sicily fragmented into several warring factions with three main emirates based in Trapani (western Sicily), Enna (central Sicily) and Syracuse (eastern Sicily).[141] After conquering western Sicily in 1053, emir Ibn al-Thumna of Syracuse struggled to defeat his brother-in-law Ibn Hawwas, the emir of Enna in central Sicily; in 1061, he therefore hired Norman mercenaries from the Hauteville family to assist him.[141] This began the Norman conquest of Sicily (1061–1091); Ibn al-Thumna was soon set aside and assassinated in 1062, although his followers largely continued supporting the Norman invasion.[141]

- Revolt of Michael V (1041–1042), after the death of emperor Michael IV the Paphlagonian of the Byzantine Empire[142]

- Peter–Aba war (1041–1044), after the deposition of king Peter the Venetian of Hungary, and the royal election of Samuel Aba to replace him. Peter fled to Austria and rallied support from Adalbert, Margrave of Austria and Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor to retake his throne. Decided at the Battle of Ménfő.

- Danish war of succession (1042–1043), after the death of king Harthacnut (Canute III) of Denmark

- Norman conquest of Maine (1062–1063), after the death of count Herbert II of Maine[143][144]

- War of the Three Sanchos (1065–1067), after the death of the Jiménez king Ferdinand I "the Great" of León (and Castile)[145]

- Harald Hardrada's invasion of England involving the Battle of Fulford and the Battle of Stamford Bridge (1066), after the death of king Edward the Confessor of England

- Norman invasion of England (1066–1075), after the death of king Edward the Confessor of England

- (historicity contested) Eric and Eric (c. 1066–1067): according to Adam of Bremen, they were two claimants who fought each other after the death of king Stenkil of Sweden. Modern historians doubt whether the two Erics even existed.[146]

- Jiménez fraternal war (1067–1072), after the death of the Jiménez queen Sancha of León, wife of the late Ferdinand I "the Great" of León (and Castile)[145]

- War of the Flemish succession (1070–1071), after the death of count Baldwin VI of Flanders

- Byzantine war of succession (1071–1072), after Byzantine emperor Romanos IV Diogenes was defeated in the Battle of Manzikert (26 August 1071) and deposed when John Doukas enthroned Michael VII Doukas in Constantinople (24 October 1071). The war consisted of the Battle of Dokeia and the Sieges of Tyropoion and Adana, all of which Romanos lost. Simultaneously, the Uprising of Georgi Voyteh (1072) took place in Bulgaria, which was also crushed by Michael VII.[147]

- Apulian-Calabrian war of succession (1085–1089), after the death of the Hauteville duke Robert Guiscard of Apulia and Calabria between his sons Bohemond I of Antioch and Roger Borsa

- Rebellion of 1088, after the death of William the Conqueror of Normandy and England

- War of the Croatian Succession (1091–1105), after the death of king Stephen II of Croatia.[148] Decided at the Battle of Gvozd Mountain (1097).

- Chernihiv war of succession (1093–1097), after the death of Vsevolod I Yaroslavich, grand prince of Kyivan Rus' and prince of Chernihiv and Pereyaslavl[149]

- Internecine war of Rus' 1097–1100, after the blinding and imprisonment of prince Vasylko Rostyslavych of Terebovlia

- Este war of succession (1097), after the death of Albert Azzo II, Margrave of Milan, founder of the House of Este. The oldest son by his second wife Garsende, Fulco I, Margrave of Milan, won the war and continued the House of Este in Italy. His son by his first wife Kunigunde of Altdorf, Welf I, Duke of Bavaria, became the founder of the House of Welf.

- Anglo-Norman war of succession (1101–1106), after the death of king William II of England

- Salian war of succession (1125–1135), after the death of Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor, the last monarch of the Salian dynasty[79]

- War of the Flemish succession (1127–1128), after the assassination of count Charles I "the Good" of Flanders

- Apulian war of succession (1127–1130), after the death of the Hauteville duke William II of Apulia and Calabria between his first cousin once removed Roger II of Sicily on the one hand, and his second cousin once removed Robert II of Capua and Ranulf II of Alife (Roger II's brother-in-law) on the other.[lower-alpha 4]

- Civil war era in Norway or Norwegian Civil War(s) (1130–1240), after the death of king Sigurd the Crusader of Norway[79]

- The Anarchy or English Dynastic War (1135–1154), after the death of king Henry I of England[142]

- German war of succession (1138–1139), after the 1137 death of Lothair III, Holy Roman Emperor and the 1138 Imperial election, between Conrad III of Germany and Henry X, Duke of Bavaria[79]

- Baussenque Wars (1144–1162), after the death of count Berenguer Ramon I of Provence

- Internecine war of Rus' 1146–1154, after the death of grand prince Vsevolod II of Kyiv

- Danish Civil War (1146–1157), after the abdication of king Eric III of Denmark

- Castilian war of succession (1158–11??), after the death of king Sancho III of Castile over the regency of his son, infant-king Alfonso VIII of Castile, between the houses of Lara and Castro. King Sancho VI of Navarre took the opportunity to rescind his vassalage to Castile, and invaded to take several territories until a truce in 1167. When Alfonso VIII came of age in 1170, he renewed hostilities to retake the Castilian lands lost during his infancy.

- Serbian war of succession (c. 1166–1168), after the brothers Tihomir of Serbia and Stefan Nemanja failed to properly share the inheritance of their father Zavida[150]

- Gwynedd war of succession (1170–1174), after the death of Owain Gwynedd, king of Gwynedd, prince of the Welsh. Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd emerged victorious.

- War of the Namurois–Luxemburgish succession (1186–1263/5), after the decades-long childless count Henry the Blind of Namur and Luxemburg, having designated Baldwin V of Hainaut his heir in 1165, after all fathered Ermesinde in 1186 and tried to change his succession in her favour. Although the struggle over Luxemburg was resolved in 1199 in favour of Ermesinde, she and Baldwin and their successors would continue to fight over Namur until it was sold to Guy of Dampierre in 1263 or 1265.[151][152]

- Sicilian war of succession (1189–1194), after the death of king William II of Sicily

- Internecine war of Rus' 1195–1196, after the death of grand prince Svyatoslav III Vsevolodovych of Kyivan Rus'

- Hungarian throne struggle (1197–1203), after the death of king Béla III of Hungary and Croatia[153]

- German throne dispute (1198–1215), after the death of Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor. Although mostly a political conflict between the House of Hohenstaufen and House of Welf, the Battle of Bouvines (1214) meant the de facto defeat of pretender-king Otto IV of Welf, deposed in 1215 in favour of anti-king Frederick II of Hohenstaufen.[154]

- Angevin war of succession (1199–1204), after the death of Richard the Lionheart of England, Normandy, Aquitaine, Anjou, Brittany, Maine and Touraine, collectively known as the Angevin Empire[155]

- The French invasion of Normandy (1202–1204) was the last part of the Angevin war of succession

- Deheubarth war of succession (1197–1201), after the death of prince Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth and Wales. Maelgwn ap Rhys emerged victorious.

- Fourth Crusade (1202–1204), was redirected to Constantinople to intervene in a Byzantine succession dispute after the deposition of emperor Isaac II Angelos

- Serbian war of succession (1202–1205), after the death of grand prince Stefan Nemanja of Serbia

- Loon War (1203–1206), after the death of Dirk VII, Count of Holland[1]

Entry of the Crusaders in Constantinople, Eugène Delacroix. The 1204 Sack of Constantinople caused a complex series of related wars of succession in Southeastern Europe and Asia Minor, as many pretenders laid claim to the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire's legacy.

- Complex series of wars of succession between the Sack of Constantinople, the deaths of emperors Isaac II Angelos, Alexios IV Angelos and Alexios V Doukas of the Byzantine Empire in 1204, and the Reconquest of Constantinople in 1261. The de facto succession came in the hands of the Latin Empire, but was challenged by Nicaea, Trebizond, Thessalonica, and Bulgaria, amongst others.

- Nicaean–Latin wars (1204–1261). Constantine Laskaris and Theodore I Laskaris were early candidates for the Byzantine emperorship, and would found the Empire of Nicaea in order to restore it.

- Nicaean war of succession (1221–1223/4), after the death of emperor Theodore I Laskaris of Nicaea

- Bulgarian–Latin wars (1204/1230–1261). Although war between them broke out almost immediately after the Latin Empire was founded, the Bulgarian monarch would not claim the Byzantine emperorship until defeating pretender Theodore Komnenos Doukas of the Empire of Thessalonica in 1230.

- Trapezuntine wars against the Latin Empire and Nicaea (1204–?). Alexios I of Trebizond proclaimed himself Byzantine emperor in April 1204 (around the Sack of Constantinople) as the legitimate heir of Andronikos I Komnenos.

- Thessalonian wars against the Latin Empire and Nicaea (1224–1242). Theodore Komnenos Doukas proclaimed himself the Byzantine emperor upon conquering Thessalonica in 1224, a direct challenge to the Latin and Nicaean pretenders.

- Nicaean–Latin wars (1204–1261). Constantine Laskaris and Theodore I Laskaris were early candidates for the Byzantine emperorship, and would found the Empire of Nicaea in order to restore it.

- Galician–Volynian War of Unification (1205–1245), after the death of Roman Mstyslavych "the Great", grand prince of Kyiv, prince of Galicia and Volynia

- Lombard Rebellion (1207–1209), after the death of king Boniface of Thessalonica

- Bulgarian war of succession (1207–1218), after the death of tsar Kaloyan of Bulgaria. Boril, Ivan Asen II, Strez, and Alexius Slav were amongst the pretenders.

- Portuguese inheritance conflict (1211–1216), after the death of king Sancho I of Portugal. Afonso II of Portugal denied his sisters Theresa of Portugal, Queen of León (supported by her ex-husband Alfonso IX of León) Sancha, Lady of Alenquer and Mafalda of Portugal a share in the inheritance, in violation of Sancho I's will, leading to war. The Leonese army of Alfonso IX supporting the three sisters and their Portuguese allies defeated the army of Afonso II and his Portuguese supporters at the Battle of Valdevez in early 1212, but then Alfonso VIII of Castile intervened in behalf of Afonso II and forced the Leonese to withdraw. Although Pope Innocent III declared peace among Christian realms and to join forces against the Muslims ahead of the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (16 July 1212), the three sisters managed to get the Pope to place Portugal under an interdict for 1.5 years in August 1212. Shortly after, Alfonso of Leon, Alfonso of Castile and Afonso of Portugal signed a truce at Coimbra and pledged mutual aid against the Muslims. Afonso's dispute with his sisters was finally settled in 1216.[156][157]

- War of the Moha succession (1212–1213), over the County of Moha after the death of count Albert II of Dagsburg

- Vladimir-Suzdal war of succession (1212–1216), after the death of grand prince Vsevolod the Big Nest of Vladimir-Suzdal

- Castilian war of succession (1214/7–1218), after the death of king Alfonso VIII of Castile and especially king Henry I of Castile, prompting a war over the regency and a Leonese invasion[158]

- First Barons' War (1215–1217). The war began as a Barons' revolt over king John Lackland's violation of the Magna Carta, but quickly turned into a dynastic war for the throne of England when French crownprince Louis became their champion, and John Lackland unexpectedly died

- War of the Succession of Champagne (1216–1222), indirectly after the death of count Theobald III of Champagne

- War of the Schlawe and Stolp succession (1223–1236), after the death of Ratibor II, Duke of Pomerania, over the Lands of Schlawe and Stolp

- War of the Succession of Breda (1226/8–1231/2), after the death of lord Henry III of Schoten of Breda[159]

- Internecine war in Rus' 1228–1240, after the death of prince Mstyslav Mstyslavych Udatnyi of Tmutorokan and Chernihiv

- Isenberg Confusions (1232–1243), traces back to the 1226 execution of count Frederick of Isenberg for the 1225 killing of archbishop Engelbert II of Cologne

- Danish war of succession (1241–124?), after the death of king Valdemar II of Denmark[142]

- War of the Flemish Succession (1244–1254), after the death of countess Joan of Constantinople of Flanders and Hainaut

- Austrian Interregnum or War of the Babenberg Succession (1246–1256/78/82), after the death of Frederick II, Duke of Austria. An important event was the Battle of Kressenbrunn (1260).

- War of the Thuringian Succession (1247–1264), after the death of landgrave Henry Raspe IV of Thuringia

- Great Interregnum (1245/50–1273), after the deposition and death of emperor Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire

- Bigorre succession crisis (1255–1302), after the death of countess Alice of Bigorre

- War of the Euboeote Succession (1256–1258), after the death of triarch Carintana dalle Carceri of Negroponte

- Bulgarian war of succession (1256–1261), after the assassination of tsar Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria

- Castilian war of succession (1282–1304): after the death of crown prince Ferdinand de la Cerda (1275) and in anticipation of the death of king Alfonso X of Castile (1284), Ferdinand's brother Sancho proclaimed himself king in 1282, while Ferdinand's sons Alfonso de la Cerda and Ferdinand de la Cerda, Lord of Lara claimed to be the rightful heirs until they rescinded their claims in 1304[160]

- War of the Limburg Succession (1283–1288), after the death of duke Waleran IV and his daughter and heiress Irmgard of Limburg

- Croato–Hungarian war of succession (1290–1301), after the death of king Ladislaus IV of Hungary and Croatia

- (uncertain) Greater Poland war of succession (1296), after the assassination of Przemysł II, king of Poland and duke of Greater Poland, on 8 February 1296. The war, if it really took place, didn't last long, because on 10 March 1296 in Krzywiń an armistice was signed.[161]

Late Medieval Europe

The Hundred Years' War arose when the English king claimed the French throne.

The 1388 Battle of Strietfield secured Lüneburg for the House of Welf.

The Battle of St. Jakob an der Sihl (1443) during the Old Zürich War.

The Catholic Monarchs united 'Spain' after the War of the Castilian Succession.

- Scottish Wars of Independence (1296–1357), after the Scottish nobility requested king Edward I of England to mediate in the 1286–92 Scottish succession crisis, known as the "Great Cause". Edward would claim that his role in appointing the new king of Scots, John Balliol, meant that he was now Scotland's overlord, and started to interfere in Scottish domestic affairs, causing dissent.[162]

- First War of Scottish Independence (1296–1328), after Scottish opposition to Edward's interference reached the point of rebellion, Edward marched against Scotland, defeating and imprisoning John Balliol, stripping him off the kingship, and effectively annexing Scotland. However, William Wallace and Andrew Moray rose up against Edward and assumed the title of "guardians of Scotland" on behalf of John Balliol, passing this title on to Robert the Bruce (one of the claimants during the Great Cause) and John Comyn in 1298. The former killed the latter in 1306, and was crowned king of Scots shortly after, in opposition to both Edward and the still imprisoned John Balliol.[162]

- Second War of Scottish Independence, or Anglo-Scottish War of Succession[163] (1332–1357), after the death of king of Scots Robert the Bruce

- Árpád war of succession (1301–1308), after the death of king Andrew III of Hungary and the extinction of the Árpád dynasty[164]

- Polish-Bohemian war (1305–1308), after the death of king Wenceslaus II of Bohemia and Poland[79]

- Brandenburgish Interregnum (1319/1320–1323), after the death of Waldemar, Margrave of Brandenburg-Stendal. See also False Waldemar.

- Byzantine civil war of 1321–28, after the deaths of Manuel Palaiologos and his father, co-emperor Michael IX Palaiologos, and the exclusion of Andronikos III Palaiologos from the line of succession

- Bredevoorter Feud (1322–1326), after the death of count Herman II of Lohn

- Wars of the Rügen Succession (1326–1328; 1340–1354), after the death of prince Vitslav III of Rügen

- Wars of the Loon Succession (1336–1366), after the death of count Louis IV of Loon

- Hundred Years' War (1337–1453), indirectly after the death of king Charles IV of France

- Galicia–Volhynia Wars (1340–1392), after the death of king Bolesław-Jerzy II of Galicia and Volhynia

- War of the Breton Succession (1341–1365), after the death of duke John III of Brittany. In practice, it became a theatre in the wider Hundred Years' War (1337–1453).[165]

- Byzantine civil war of 1341–47, after the death of emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos[158]

- Byzantine civil war of 1352–1357, resumption of the 1341–47 war after the compromise peace of three emperors ruling simultaneously broke down

- Thuringian Counts' War (1342–1346), continuation of the War of the Thuringian Succession (1247–1264)

- Neapolitan campaigns of Louis the Great (1347–1352), after the assassination of Andrew, Duke of Calabria one day before his coronation as king of Naples

- Hook and Cod wars (1349–1490), after the death of count William IV of Holland

- Guelderian Fraternal Feud (1350–1361), after the death of duke Reginald II of Guelders

- Castilian Civil War (1351–1369), after the death of king Alfonso XI of Castile

- War of the Two Peters (1356–1375), spillover of the Castilian Civil War and Hundred Years' War

- War of the Valkenburg succession (1352–1365), after the death of lord John of Valkenburg[166]

- War of the Brabantian Succession (1355–1357), after the death of duke John III of Brabant

- Neuenahr war of succession (1358–1382), after the death of count William III of Neuenahr

- Golden Horde Dynastic War (1359–1381)[133] after the assassination of khan Berdi Beg of the Golden Horde

- Fernandine Wars (1369–1382), fought over king Ferdinand I of Portugal's claim to the Castilian succession after the death of king Peter of Castile in 1369

- First Fernandine War (1369–1370)

- Second Fernandine War (1372–1373)

- Third Fernandine War (1381–1382)

- War of the Lüneburg Succession (1370–1389), after the death of duke William II of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- The three Guelderian wars of succession:

- First War of the Guelderian Succession (1371–1379), after the death of duke Reginald III of Guelders

- Second War of the Guelderian Succession (1423–1448), after the death of duke Reginald IV Guelders and Jülich

- Third War of the Guelderian Succession (1538–1543), see Guelders Wars (1502–1543)

- Władysław the White's rebellion (1373–1377), after the death of king Casimir III the Great of the United Kingdom of Poland between Władysław the White and Louis I of Hungary

- Lithuanian war of succession (1377–1387), after the death of grand duke Algirdas of Lithuania, between his son and designated heir Jogaila and his other son Andrei of Polotsk.

- Lithuanian Civil War (1381–1384), broke out when Algirdas' brother Kęstutis rebelled against Jogaila and claimed the throne for himself while Jogaila was besieging Andrei at Polotsk.

- War of the Succession of the Patriarchate of Aquileia (1381–1388), after the death of patriarch Marquard of Randeck

- Greater Poland Civil War (1382–1385), after the death of king Louis the Hungarian of Poland[79]

- 1383–1385 Portuguese interregnum, Portuguese succession crisis and war after the death of king Ferdinand I of Portugal

- Ottoman Interregnum (1401/2–1413), after the imprisonment and death of sultan Bayezid I

- Everstein Feud (1404–1409), after the childless count Herman VII of Everstein signed a treaty of inheritance with Simon III, Lord of Lippe, which was challenged by the Dukes of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Aragonese Interregnum (1410–1412), after the death of king Martin of Aragon

- Neapolitan war of succession (1420–1442), after the death of king Martin of Aragon (who also claimed Naples) and resulting from the childless queen Joanna II of Naples's subsequent conflicting adoptions of Alfonso V of Aragon, Louis III of Anjou and René of Anjou as her heirs.[79] Some scholars posit the war's start as having begun with Joanna's death in 1435, and name it the 'Aragonese–Neapolitan War'.[167]

- (contested) Hussite Wars (1419–1434): some scholars claim that the death of king Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia on 19 August 1419 is the event that sparked the Hussite rebellion against his nominal successor Sigismund (king of Germany, Hungary and Croatia).[142] In 1420, Hussites offered the Bohemian crown to Władysław II Jagiełło instead.[168] Nolan (2006) summarised the Hussites' motives as 'doctrinal as well as "nationalistic" and constitutional', and provided a series of causes: the trial and execution of Jan Hus (1415) 'provoked the conflict', the Defenestration of Prague (30 July 1419) 'began the conflict', while 'fighting began after King Wenceslaus died, shortly after the defenestration' (after 19 August 1419).[169] Nolan described the wars' goals and character as follows: 'The main aim of the Hussites was to prevent the hated Sigismund mounting the throne of Bohemia, but fighting between Bohemian Hussites and Catholics spread into Moravia. (...) cross-class support gave the Hussite Wars a tripartite and even "national" character unusual for the age, and a religious and social unity of purpose, faith, and hate'.[170] Winkler Prins/Encarta (2002) described the Hussites as a 'movement which developed from a religious denomination to a nationalist faction, opposed to German and Papal influence; in the bloody Hussite Wars (1419–1438), they managed to resist.' It didn't mention the succession of Wenceslaus by Sigismund,[171] but noted elsewhere that it was Sigismund's policy of Catholic Church unity which prompted him to urge Antipope John XXIII to convene the Council of Constance in 1414, which ultimately condemned Jan Hus.[172]

- Muscovite War of Succession, or Muscovite Civil War (1425–1453), after the death of grand prince Vasily I of Muscovy[79][173]

- Lithuanian Civil War (1432–38), after the death of grand duke Vytautas the Great of Lithuania

- Polish–Bohemian war (1437–143?), after the death of king Sigismund of Bohemia.[142] He was supposed to be succeeded by Albert II of Germany, but in 1438, the Czech anti-Habsburg opposition, mainly Hussite factions, offered the Czech crown to Polish king Jagiełło II's younger son Casimir instead.[168] The idea, accepted in Poland over Zbigniew Oleśnicki's objections, resulted in two unsuccessful Polish military expeditions to Bohemia.[168] Included the Battle of Sellnitz.

- Habsburg Dynastic War (1439–1457), after the death of Albert II of Germany[174][142]

- Hungarian war of succession (1439–1442), after the death of Albert II of Germany[142]

- Old Zürich War (1440–1446), after the death of count Frederick VII of Toggenburg

- Saxon Fratricidal War (1446–1451), after the death of landgrave Frederick IV of Thuringia

- Milanese War of Succession (1447–1454), after the death of duke Filippo Maria Visconti of the Duchy of Milan[175][176]

- Scandinavian war of 1448–1471, after the death of king Christopher III of the Kalmar Union (Denmark, Sweden and Norway)[79]

- Navarrese Civil War (1451–1455), after the death of Blanche I of Navarre and the usurpation of the throne by John II of Aragon

- The Utrecht wars, related to the Hook and Cod wars.

- Utrecht Schism (1423–1449), after the death of prince-bishop Frederick of Blankenheim of Utrecht

- Utrecht war (1456–1458), after the death of prince-bishop Rudolf van Diepholt of Utrecht

- Utrecht war (1470–1474), aftermath of the 1456–58 Utrecht war

- Utrecht war of 1481–83 (1481–1483), spillover of the Hook and Cod wars

- Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), after the weakness of (and eventually the assassination of) king Henry VI of England

- War of the Neapolitan Succession (1458–1462), after the death of king Alfonso V of Aragon

- Skanderbeg's Italian expedition (1460–1462)

- Cypriot war of succession (1460–1464), after the death of king John II of Cyprus

- Hesse–Paderborn Feud (1462–1471), after the death of lord Rabe of Calenberg

- Catalan Civil War (1462–1472), after the death of crown prince Charles, Prince of Viana (1461) and the deposition of king John II of Aragon (1462) by the Consell del Principat, who offered the crown to several other pretenders instead

- War of the Succession of Stettin (1464–1529), after the death of duke Otto III of Pomerania

- Burgundian conquest of Guelders (1473), after the death of duke Arnold of Egmont of Guelders[177]

- Hessian Fratrical War (1469–1470), after the 1458 death of Louis I, Landgrave of Hesse[178]

- War of the Castilian Succession (1475–1479), after the death of king Henry IV of Castile[167]

- War of the Głogów Succession (1476–1482), after the death of duke Henry XI of Głogów[179]

- War of the Burgundian Succession (1477–1482), after the death of duke Charles the Bold of Burgundy

- Guelderian War of Independence (1477–1482, 1494–1499), after the death of duke Charles the Bold of Burgundy

- Ottoman war of succession (1481–1482), between prince Cem and prince Bayezid after the death of sultan Mehmet II[79]

- Mad War (1485–1488), about the regency over the underage king Charles VIII of France after the death of king Louis XI of France

- French–Breton War (1487–1491), anticipating the childless death of duke Francis II of Brittany (died 1488). Essentially, it was a resumption of the War of the Breton Succession (1341–1364)

- War of the Granada succession (1482–1492), after the deposition of emir Abu'l-Hasan Ali of Granada by his son Muhammad XII of Granada; the deposed emir's brother Muhammad XIII of Granada also joined the fight. This succession conflict took place simultaneously with the Granada War, and was ended only by the Castilian conquest in 1492.[180]

- Jonker Fransen War (1488–1490), last ignition of the Hook and Cod wars

- War of the Hungarian Succession (1490–1494), after the death of king Matthias Corvinus I of Hungary and Croatia[181]: 3:57

- Italian War of 1494–1495 or Italian War of Charles VIII, after the death of king Ferdinand I of Naples[182]

Early Modern Europe

The Jülich Succession became a European war, because the future religious balance of power depended on it.

During the War of the Spanish Succession, a large European coalition tried to keep Spain out of French hands.

The War of the Austrian Succession grew out to an almost pan-European land war, spreading to colonies in the Americas and India.[183]

- War of the Katzenelnbogen Succession (1500–1557; German: Katzenelnbogener Erbfolgekrieg/Erbfolgestreit), after the death of count William III, Landgrave of Hesse[184][185]

- Hadamar succession struggle (1371–1557; German: Hadamarer Erbfolgestreit), after the 1368 death of regent Henry of Nassau-Hadamar and the insanity of nominal count Emicho III of Nassau-Hadamar. The conflict merged into the War of the Katzenelnbogen Succession.

- War of the Succession of Landshut (1503–1505), after the death of duke George of Bavaria-Landshut

- Ottoman Civil War (1509–13), between prince Selim and prince Ahmed about the succession of sultan Bayezid II (died 1512)

- Danish Wars of Succession (1523–1537), a series of conflicts about the Danish throne within the House of Oldenburg

- Danish War of Succession (1523–1524), because of dissatisfaction about the kingship of Christian II of Denmark, who was deposed; indirectly caused by the death of king John (Hans) of Denmark in 1513 (see also Siege of Copenhagen (1523))

- Count's Feud (1533/4–1536), after the death of king Frederick I of Denmark[142]

- Little War in Hungary (1526–1538), after the death of king Louis II of Hungary and Croatia between Ottoman vassal-king John Zápolya of "Eastern Hungary" and king Ferdinand I of Habsburg of "Royal Hungary"[186]

- Italian War of 1536–1538, after the death of duke Francesco II Sforza of Milan

- Little War in Hungary (1540–1547), after the death of Ottoman vassal-king John Zápolya of "Eastern Hungary" between his son and successor John Sigismund Zápolya and king Ferdinand I of Habsburg of "Royal Hungary". The first battle was the Siege of Buda (1541).[186]

- Wyatt's rebellion (1553–1554), after recently acceded Mary I of England's decision to marry the non-English Catholic prince Philip II of Spain.[187] See also Northumberland's insurrection (July 1553), after the death of king Edward VI of England and Ireland, which never became a war.

- Ottoman war of succession of 1559, between prince Selim and prince Bayezid about the succession of sultan Süleyman I