Damalas

The House of Damalas (pl. Damalases; Greek: Δαμαλάς, pl. Δαμαλάδες, female version Damala; Greek: Δαμαλά) is a Greek Noble House with roots originating from the island of Chios. Created as a result of intermarriages among the Imperial House of Palaiologos to the Genoese Noble House of Zaccaria.[1][2][3][4] Officially established in the 14th century, though there was also an unrelated ancient Greek House named Damalas as well, which had settled in Byzantium long before the 330 A.D. establishment of the Eastern Roman Empire. Descendants of this unrelated house were also settled on the Aegean island of Kos.

Chiot Aristocracy

Scholars have determined that the qualities defining the Byzantine aristocrat were established as early as the eighth century: primarily by virtue of birth and by virtue of moral and spiritual qualities. Military and civil officers who rendered services to the emperor were held in high esteem occupying a high position in the social pyramid. They derived their revenues from grants of land as a reward for their services. Aristocratic wealth came from three sources: personal wealth, gifts of land from the emperor, and high-ranking positions and offices to which "rogai" were attached. Land donations from emperors reached their apogee in the Palaiologan period. The greatest landlords who possessed vast stretches of land were the Church and the monasteries.[5]

The eugeneia (nobility) of the lineage and the perpetuation of the oikos-house were secured through alliances and intermarriages between members of the great families. According to Angold, the heyday of the Byzantine aristocracy was the age of the Komnenoi (early 12th century), during which the top of the social pyramid was divided between two groups: the great noble families, who were active in the army or served in the imperial bureaucracy, and local families who were the leaders of the provincial towns. The mikroi occupied the base of the social pyramid. They were independent peasant proprietors, holders of small land parcels, free from obligations. Others were the Paroikoi, namely tenants, who paid rent for the land they cultivated.[6][7]

There are a variety of western sources for the documentation of the Genoese period of Chios; Byzantine evidence on the great families includes historiography and sigillography. Chios prided herself on having her own aristocracy by birth, confirmed by the possession of land. The Chiot gentry originated from the greatest families of Byzantium. As early as the fourteenth century, their class was enlarged with the arrival of the Genoese rulers who dominated the island's life until the mid-sixteenth century. [8]

The late medieval Chiot upper class was broken down into the following hierarchical scheme: a) Byzantine aristocrats, b) Genoese families that settled in the island in the aftermath of the conquest, and c) the Chiot-Genoese families. Co-existence of Genoese and Chiots first began in the mid-thirteenth century with the Treaty of Nymphaeum (1261) and the setting up of a Genoese emporium on Chiot soil. The establishment of the Genoese from the early fourteenth century onwards, brought about expansion of the Chiot social pyramid. Intermarriages between the locals and the settlers became frequent, bringing about the third division of the highest echelons of the Chiot aristocracy.[9]

The Chiot archontes had a decisive role in the life of the island. Their lineage and position in local administration made them the natural community leaders. They held high military offices and enjoyed court titles. The archontes showed their prominent status in different ways. Either by erecting lavishly decorated residences in distinct areas of the town, or by their insignia which decorated their dwellings, their family shrines, and the funerary monuments. This was a means to perpetuate the name of the oikos-house. The sense of genealogy was much developed. Some personal archives of surviving families' descendants of whom are traced even in our days, provide evidence for that. Those family archives were the most important and richest sources for the prosopography, organization and evolution of the Chiot medieval social stratification. Unfortunately, a large percentage of them vanished in the 1822 massacre.[10]

First references to the Noble Houses of Chios

The first study of history of the Chiot aristocratic houses is owed to Karl Hopf, who first produced a monograph on the oikos of the Giustiniani, the rulers of the second and longest Genoese occupation (1346-1566).[11] G. Zolotas is credited for the first compilation of the medieval Chiot prosopography, which occupies a separate section in his "History of Chios"; it comprises all the Chiot and Genoese lineages from the tenth century until the very end of the Genoese period.[12]

The catalogue describes also the origins of the houses, which altogether comprised the Chiot upper class. According to his estimations, the narrow circle of the Chiot aristocrats was already established in the Komnenian period. E. Malamut uses the evidence of four 11th-century lead seals connected with Chios (three seals of strategol and one of a nobelissimos)" But the specimen is too small and chronologically limited to be taken seriously into consideration.[13]

The oldest historical mention of an archon of Chios is the testimony of John Kantakouzenos, who writes that the governor of the island during the period of the Zaccaria, was Leo Kalothetos, the most important of all the Chiot magnates. As a high imperial official, Kantakouzenos was a very close friend of Kalothetos. The latter held the governorship until 1340, when the emperor dismissed him from his office on account of a hostility that sprang against his person from the part of the Grand Domestikos Kantakouzenos and Apokaukos. The governorship of the island then passed to the hands of Kaloyannis Zyvos (or Cibo or Ziffo, as mentioned in the Genoese sources).[14]

The next most significant and probably the oldest source recording the Chiot archontes is the treaty of concession of 1346. The treaty bears the terms and conditions agreed between the protagonists of the two parts followed by their signatures. On the one hand, the Admiral Simone Vignoso signed on behalf of the Commune of Genoa. On the other, prominent members of the Chiot aristocrats, as representatives of the whole body of the inhabitants of the island. Among the first terms the fifth clause was highly favorable for the interests of the Chiot aristocracy because it "safeguarded the privileges and possessions... which this class acquired from purchase, inheritance or grants from the Byzantine Emperors with chrysobulls." The Chiot aristocrats would adhere to the terms of the conventions imposed on them and the Genoese would recognize their class as hereditary and would respect them.[15]

The Chiot signatories were: the Governor Kaloyannis Zyvus (Cibo or Ziffo), the Great Falconer Argenti, Constantine Zyvos (Cibo or Ziffo), the Grand Sakellarios Michael Koressios (Coressi), Sevastos Coressi (Syndicus), Georgio Agelastos (Syndicus et procuratore) and the "Protocomes Damala" (Baron of Damala).[16][17]

How they assumed the power and became governors of the island is recorded again by John Kantakouzenos. The political crisis in the early fourteenth century caused by the civil war between Andronikos II and Andronikos III coincided with the possession of Chios, at that time by the Zaccaria family (1304-1329). The emperor held the sovereignty of the island but conceded the administration to Benedetto Zaccaria (and, after his death, to his successors) with a renewable lease. The expulsion of the latters' heir, Martino Zaccaria, in 1329 had a major repercussion on the island as it allowed the concession of the political power to the hands of the local magnates. It is likely that even prior to that period the conditions must have been the same, with the island in a state of semi-autonomy or autonomy and the concentration of power to the magnates. The sources clarify that the Chiot aristocrats were so powerful that they practically governed the island, albeit in theory in the name of the Byzantine Emperor. During the brief Byzantine repossession (1329-1346), the emperor appointed five of the most illustrious local families to govern Chios in his name. Those were: Kalothetos, Zyvos (Ziffo or Cibo), Argenti, Koressios (Coressi), and Damala (Damalas). This is the first historical recording of the nucleus of the closed Chiot aristocratic circle, dubbed "The Quintet."[18] The treaty of submission is more valuable, because it is the first official recording of names of indigenous local magnates, and their offices.[19]

The family during the Byzantine Reconquest of Chios

The Byzantine rulers had little influence over Chios and through the Treaty of Nymphaeum, authority was ceded to the Republic of Genoa (1261).[20] At this time the island was frequently attacked by pirates, and by 1302–1303 was a target for the renewed Turkish fleets. To prevent Turkish expansion, the island was reconquered and kept as a renewable concession, at the behest of the Byzantine emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos, by the Genoese Benedetto I Zaccaria (1304), then admiral to Philip of France. Zaccaria installed himself as ruler of the island, founding the short-lived Lordship of Chios. His rule was benign and effective control remained in the hands of the local Greek landowners. Benedetto Zaccaria was followed by his son Paleologo and then his grandsons Benedetto II and Martino.

In 1327 Martino took part in alliance negotiations between the Byzantines and the Republic of Venice.[21] At the same time, however, Martino's behavior became increasingly assertive. In 1325 he ousted his brother as co-ruler of Chios and began minting coins in his own name.[22][23] By this time the Zaccaria family had become one of the wealthiest houses in the region. Confirmation of the growing wealth of the family comes from the account of John Kantakouzenos, who claimed that by the late 1320s the income of Martino Zaccaria had reached 120,000 hyperpyra per year; which has been estimated to equate to roughly one-fifth of the annual Byzantine Imperial Revenue under the reign of Andronikos III.[24][25] In 1328, the rise of this new and energetic emperor to the Byzantine Throne marked a turning-point in relations. One of the leading Chiot nobles, Leo Kalothetos, went to meet the new emperor and his chief minister, John Kantakouzenos. He proposed a reconquest of the island and Andronikos III readily agreed. On the pretext of Martino's unauthorized building of a new fortress on the island, the emperor sent him a letter, in which he ordered him to cease construction and present himself in Constantinople within the next year in order to renew the island's lease. Martino haughtily rejected the demands and accelerated construction. But now his deposed brother Benedetto lodged a complaint with the emperor claiming that his share of one-half of the island's revenues was his and was due. With these events as an excuse, in autumn 1329 Andronikos III assembled a fleet of 105 vessels—including the forces of the Latin Duke of Naxos, Nicholas I Sanudo—and sailed to Chios.[26]

Even after the imperial fleet reached the island, Andronikos III offered to let Martino keep his possessions in exchange for the installation of a Byzantine garrison and the payment of an annual tribute, but Martino refused. He sank his three galleys in the harbor, forbade the Greek population to bear arms and locked himself with 800 men in his citadel, where he raised his own banner instead of the emperor's. His will to resist was broken, however, when Benedetto surrendered his own fort to the Byzantines, and when he saw the locals welcoming them, he was soon forced to surrender. The emperor spared his life, even though the Chiots demanded his execution, and took him prisoner to Constantinople. Martino's wife and family were allowed to maintain part of their wealth, and most of the Zaccaria adherents chose to stay on the island as imperial officials; namely his sons Bartolemmeo and Centurione. Benedetto was offered the island's governorship, but he obstinately demanded to receive it as a personal possession in the same way as his brother had held it, a concession the emperor was unwilling to grant. Benedetto retired to the Genoese colony of Galata, from where a few years later he made an unsuccessful attempt to reclaim Chios; he died soon after. Andronikos III appointed Kalothetos as the new governor of Chios, and followed up his success by sailing to Phocaea, forcing it to acknowledge his suzerainty.[27][28]

Aftermath and eventual repossession of Chios

Of Martino's two sons, Bartolomeo died in 1334. His other son Centurione inherited his father's possessions in Morea, which he ruled until his death. He was awarded the title of Baron of Damala during his father's imprisonment in Constantinople as early as 1336. This began the dynastic struggle of the local baronies on the death of Philip of Taranto.

In thirteenth and fourteenth century France, a Baron was a lower member of the nobility. In the Principality of Achaea however, Barons were high lords, akin to a Duke. As such, they held their authority directly from the Prince and the principality consisted of twelve large baronies. One of these baronies was Damala, being located on the eastern coast of Morea and controlling the entirety of the argolid peninsula.

By supporting Roberto son of Filippo, Centurione obtained the recognition of his sovereignty and the confirmation of his rights violated several times in the past by the Angioni princes. His father Martino had continued the system of alliances through the marriages of his own children. Bartolomeo married Guglielma Pallavicino, who had brought the Marquis of Bodonitsa as a dowry. Centurione married the daughter of the governor of Byzantine Morea, Andronikos Asen, in turn son of the Bulgarian Tsar Ivan Asen III and Irena Palaiologina daughter of Michael VIII Palaiologos and sister of Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos. This Imperial marriage linked the Zaccarias to the Imperial houses of Byzantium and Bulgaria, consolidating the aims of the family as a princely dynasty. Centurione on the death of his father in 1345, had also inherited the baronies of Chalandritsa. As well as the fortresses of Stamira and Lysaria, which he further strengthened with the marriage of his son Andronikos Asen Zaccaria with the only daughter of the powerful baron of Arcadia and Saint-Sauveur, Erard III Le Maure.

Local rule in Chios was brief. In 1346, a chartered company controlled by the Giustiniani called "Maona di Chio e di Focea", was set up in Genoa to reconquer and exploit Chios and the neighboring town of Phocaea in Asia Minor. Although the islanders firmly rejected an initial offer of protection, the island was invaded by a Genoese fleet, led by Simone Vignoso, and the castle besieged.

Combining information from historians such as G. Zolotas, C. Pagano, and A. Damalas and their works: "History of Chios" 1924, "Giustiniani of Chios" 1846, "The Economic Life of the Island of Chios" 1998, respectively, it is worth focusing on the siege of the island. Most notably the transfer of power from the island's local rulers to the Genoese Admiral on the 12th of September, 1346. On that same day two treaties were drafted, but not signed by the Baron of Damala, Centurione Zaccaria de Damala. Whom was now scion of the great Genoese Noble House of Zaccaria; by which time had grown powerful.

Centurione did not wait for the arrival of the diplomats, sent by the Empress Anne in order to negotiate with those under Admiral Vignoso. He mounted a resistance to the siege, however after several months, had to surrender the island to prevent starvation as a result of their naval blockade; though he did not sign the capitulation. Prior to the surrender being formalized, drafted by I.N. of Agios Nikolaos, he escaped with 6 of his sailors and headed for Byzantine territory in Phocaea in order to organize an operation to retake the island of Chios. This forced the Genoese Admiral to sign for Centurione in his absence "Protocomes Damala" as Centurione was Baron of Damala by this time. On the same day a second treaty was signed. In this treaty he granted amnesty to Centurione and all the privileges granted by chrysobulls of Byzantine emperors, as well as the religious freedom of Orthodox Christians in Chios. It is worth noting that even the Senate of Genoa apologized to the Byzantine Royal Commissioner (Viceroy) Anna for the raid by Admiral Vignoso which was not officially sanctioned.

The beginning of Damalas as a surname

Centurione and his descendants ruled the Barony of Damala in the Morea after their expulsion from Chios. As such, his children adopted "de Damala" onto their surnames.[29][30] It is well documented what became of his eldest son Andronikos and his descendants; as well as his daughter Maria because of her notable marriage. However, there are less sources for his other three sons: Filippo, Manuele and Martino.[31] It is possible that Martino could have been the same person as Manuele as he does not appear in most genealogical records; he is known only from his participation in the Battle of Gardiki in 1375.[32] Filippo and Manuele are well documented through their marriages to prominent women of the time.[33] It is through either of these sons or both that the "Damala" (later Hellenized to Damalas) surname in Chios comes into use.

Though the Barony appears to be lost to the family after the death of Centurione, his sons and descendants retained Damala as a surname. This served as a means of identification of where the family was from, which was common during the earlier stages of surname adoption. It is important to note, that during this time it was also common for servants to adopt the name of their Lord. Therefore, there must be a distinguishment between the modern day descendants of these servants and the actual descendants of the Noble House. In 2006, Dimitri Lainas conducted a study compiling the family tree of the Noble House and it was published in Pelinnaeo Magazine.

The Damalases remained a prominent noble family throughout the centuries often being cited in the codes and laws of the island. Producing many affluent land owners, bankers, shipping magnates and holders of political office. However the family would never attain the status that it had during its peak, when they controlled the Argolid peninsula, Chios and entire regions of the Aegean.[34][35]

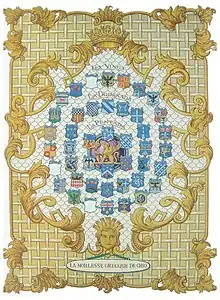

This can be seen during the first half of the 16th century with the narrow Chiot aristocratic circle crystallizing. With the enrollment of the families, which comprised it, in the Golden Key of Chios. Although the Damalases were of the original "Quintet", they fell to a lower tier of the ruling houses after losing their great lands and wealth in the Morea more than a century prior. Thirty seven families belonged to this circle, according to Argenti, who reconstructed the genealogical trees based on fragments of lost family archives and interviews of descendants. The order is as follows: the "Quintet": Argenti, Mavrogordato, Petrocochino, Rodocanachi and Schilizzi. The "Twelve", in which belonged the Agelasto, Vouro, Galati, Grimaldi, Calvocoressi, Condostavlo, Coressi, Negroponte, Ralli, Sevastopoulo, Prassacachi, and Scaramanga. And the "Twenty", Avierino, Viasto, Damalas, Ziffo, Zygomala, Casanova, Calouta, Carali, Castelli, Maximo, Paspati, Paterii, Roidi of Athens, Salvago, Sgouta, Sechiari, Scanavi, Zizinia, Franghiadi, and Chryssovelori.[36][37][38]

Church of the Holy Apostles

The Church of the Holy Apostles is a late Byzantine church located in Pyrgi, the largest medieval village of Chios. It is one of the best preserved examples of Byzantine architecture in Greece. The church originally existed as one of the personal shrines of the Damalas family, from which it is believed Pyrgi was built around. In the late Byzantine period, population centers began around churches with a tower and manor house.[39] As such, the church is situated just northeast of the village's main square.

Holy Apostles is a small reproduction of the katholicon (main church) of Nea Moni, being richly decorated outside with brick patterns. The interior is completely covered with frescoes painted by Antonios Kenygos of Crete, in 1665. An inscription over the main entrance of the church tells us that monk Symeon of the Damalas family, who eventually became the metropolitan bishop of Chios, raised the church "from its foundations" in 1564.[40] This most likely refers to an extensive renovation, since its architectural and morphological features indicate that it was constructed in the middle of the 14th century.

It is likely that the original church was destroyed in one of the great earthquakes of 1546, and thus 18 years later, Symeon came to it in ruins. Under the property law at the time, it would have belonged to his family and would have been his obligation to rebuild it.[41]

The manor house and fortified tower that accompanied the church were destroyed like many structures in the 1881 Chios earthquake.

The Massacre of Chios in 1822

Though the Damalases remained one of the most prominent houses in Chios, they abruptly lost their standing during the 1822 massacre. Ioannis Zanni Damalas, who was the governor of the island, was beheaded in the capitol of Chios. With irreparable damage done and centuries old estates and riches lost, the Damalases would nevertheless attain great wealth and social status once again in less than half a century. With individuals such as the shipping magnate and mayor twice over Ambrosios Ioannou Damalas and the mayor of Chios from 1878 to 1882 Ioannis Zanni Damalas standing out in history.[42][43]

The House of Damalas in modern day

While members of the noble house are few, the Damalases have made great strides in recent years to bring about former distinction. In 2012, Anastasia Damala formed the philanthropic Damalas Foundation which hosts intellectual seminars on the sciences, philosophy, current events and history. These seminars are held in a 8-story building located in Piraeus which houses a library, museum, chapel, several offices and 2 conference halls. The foundation currently only has operations in Piraeus, but has plans to expand with a second location in Chios on the family's Karfas estate.[44][45]

Drawing upon their noble lineage, the House of Damalas also holds a senatorial seat of the Roman State. Legally revived in Greece in 2004, it follows original Byzantine legislation and etiquette.

Notable members

- Centurione I Zaccaria de Damala, Baron of Damala in the Principality of Achaea; mid 14th century.

- Andronikos Asen Zaccaria de Damala, Lord in the Principality of Achaea; late 14th century.

- Symeon Damalas, Bishop of Chios; mid 16th century.

- Loucas Damalas, Voivode of Mykonos; late 17th century.

- Ioannis Zanni Damalas, Governor of Chios; early 19th century.

- Konstantinos Damalas, Greek revolutionary during the Greek war of independence; early 19th century.

- Ambrosios Ioannou Damalas, Shipping magnate and Mayor of Hermoupolis from 1853 to 1862.

- Aristides Damalas, Diplomat, military officer, actor, socialite and husband of Sarah Bernhardt; late 19th century.

- Nicolaos Damalas, Theologian and university professor; mid to late 19th century.

- Ioannis Zanni Damalas, Mayor of Chios from 1878 to 1882.

- Pavlos Damalas, Commercial agent and politician, Mayor of Piraeus from 1903 to 1907 and founder of the Erete Sports Club

- Tereza Damala, Socialite, lover of Ernest Hemingway and Prince Gabriele D'Annunzio, model of Pablo Picasso in the early 20th century. Subject of the historical novel "Tereza", by Freddy Germanos.

- Mikes Damalas, cinematographer; mid 20th century.

- Antonios Damalas, Scientist, professor, researcher and writer; mid-late 20th century.

- Anastasia Damala, Professor, philanthropist and founder of the Damalas Foundation.

References

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press. pp. 75–76.

- Miklosich, Franz (1860–1890). "Acta et Diplomata Graeca Medii Aevi Sacra et Profana". Vol. 4, "Acta et Diplomata Monasteriorum et Ecclesiarum Orientis Tomus Primus". Berlin, Germany: Vindobonae, C. Gerold. pp. 35 and 94.

- Battista de Burgo, Giovanni (1686). Viaggio di cinque anni in Asia, Africa, & Europa del Turco. Milan: Giuseppe Cossuto. pp. 323–332. ISBN 9789754282542.

- Missailidis, Anna (2012). THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY APOSTLES IN THE VILLAGE OF PYRGI ON CHIOS (Thesis). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. pp. 49–51, 56.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 69. ISBN 9781789697476.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 69. ISBN 9781789697476.

- Angold, Michael (1984). The Byzantine Aristocracy, IX to XIII Centuries. British Archaeological Reports (Oxford) Ltd. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9780860542834.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 69. ISBN 9781789697476.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 72. ISBN 9781789697476.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 70. ISBN 9781789697476.

- Hopf, Carl (1888). Les Giustiniani, dynastes de Chios: étude historique. Ernest Leroux.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 70. ISBN 9781789697476.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 70. ISBN 9781789697476.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 70. ISBN 9781789697476.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. pp. 70, 71. ISBN 9781789697476.

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press. pp. 4, 27.

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press. pp. 75–76.

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press. pp. 4, 27.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. pp. 70, 71. ISBN 9781789697476.

- William Miller, "The Zaccaria of Phocaea and Chios. (1275–1329.)" The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 31, 1911 (1911), pp. 42–55; doi:10.2307/624735.

- Miller, William (1921). "The Zaccaria of Phocaea and Chios (1275-1329)". Essays on the Latin Orient. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 290. OCLC 457893641.

- Miller, William (1921). "The Zaccaria of Phocaea and Chios (1275-1329)". Essays on the Latin Orient. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 291. OCLC 457893641.

- Trapp, Erich; Walther, Rainer; Beyer, Hans-Veit; Sturm-Schnabl, Katja (1978). "6495. Zαχαρίας Μαρτῖνος". Prosopographisches Lexikon der Palaiologenzeit (in German). Vol. 3. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-7001-3003-1.

- Kantakouzenos, John (c. 1356). Historiarum (Vol. 1 ed.). pp. 371, 379–80. ISBN 9781108043731.

- Hopf, Carl (1888). Les Giustiniani, dynastes de Chios: étude historique. Ernest Leroux. p. 21.

- William Miller, "The Zaccaria of Phocaea and Chios. (1275–1329.)" The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 31, 1911 (1911), page 291; doi:10.2307/624735.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993). The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453 (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-0-521-43991-6.

- William Miller, "The Zaccaria of Phocaea and Chios. (1275–1329.)" The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 31, 1911 (1911), pages 292-294; doi:10.2307/624735.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin, Germany: Librairie de Weidmann. p. 472.

- Missailidis, Anna (2012). THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY APOSTLES IN THE VILLAGE OF PYRGI ON CHIOS (Thesis). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. pp. 49–51, 56.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin, Germany: Librairie de Weidmann. p. 502.

- Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque: recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe (1205-1430). E. de Boccard. pp. 252, 708.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin, Germany: Librairie de Weidmann. p. 502.

- Battista de Burgo, Giovanni (1686). Viaggio di cinque anni in Asia, Africa, & Europa del Turco. Milan: Giuseppe Cossuto. pp. 323–332. ISBN 9789754282542.

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press. pp. 75–76.

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 71. ISBN 9781789697476.

- Battista de Burgo, Giovanni (1686). Viaggio di cinque anni in Asia, Africa, & Europa del Turco. Milan: Giuseppe Cossuto. pp. 323–332. ISBN 9789754282542.

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press. pp. 75–76.

- Missailidis, Anna (2012). THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY APOSTLES IN THE VILLAGE OF PYRGI ON CHIOS (Thesis). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. pp. 55–56.

- Missailidis, Anna (2012). THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY APOSTLES IN THE VILLAGE OF PYRGI ON CHIOS (Thesis). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. pp. 38, 40–42, 47–48.

- Missailidis, Anna (2012). THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY APOSTLES IN THE VILLAGE OF PYRGI ON CHIOS (Thesis). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. p. 266.

- Shupp, Paul F. (1933). "Review: Argenti, Philip P. The Massacre of Chios". Journal of Modern History. 5 (3): 414. doi:10.1086/236057. JSTOR 1875872.

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press. pp. 75–76.

- Πειραιωτών, Φωνή. "ΙΔΡΥΜΑ ΓΙΑ ΤΟΝ ΠΟΛΙΤΙΣΜΟ, ΤΗΝ ΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΗ, ΤΗΝ ΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑ". Η ΦΩΝΗ ΤΩΝ ΠΕΙΡΑΙΩΤΩΝ. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Γαΐλα, Τασσώ. "Πολιτιστικό Ίδρυμα Δαμαλά!". Tο μοσχάτο μου. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

Sources

- Koukouni, Ioanna (2021). Chios dicta est... et in Aegæo sita mari: Historical Archaeology and Heraldry on Chios. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9781789697476.

- William Miller, "The Zaccaria of Phocaea and Chios. (1275–1329.)" The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 31, (1911); doi:10.2307/624735

- Miller, William (1921). "The Zaccaria of Phocaea and Chios (1275-1329)". Essays on the Latin Orient. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 457893641.

- Trapp, Erich; Walther, Rainer; Beyer, Hans-Veit; Sturm-Schnabl, Katja (1978). "6495. Zαχαρίας Μαρτῖνος". Prosopographisches Lexikon der Palaiologenzeit (in German). Vol. 3. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-7001-3003-1.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993). The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453 (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43991-6.

- Shupp, Paul F. (1933). "Review: Argenti, Philip P. The Massacre of Chios". Journal of Modern History. 5 (3). doi:10.1086/236057. JSTOR 1875872.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin, Germany: Librairie de Weidmann.

- Miklosich, Franz (1860–1890). "Acta et Diplomata Graeca Medii Aevi Sacra et Profana". Vol. 4, "Acta et Diplomata Monasteriorum et Ecclesiarum Orientis Tomus Primus". Berlin, Germany: Vindobonae, C. Gerold.

- Πειραιωτών, Φωνή. "ΙΔΡΥΜΑ ΓΙΑ ΤΟΝ ΠΟΛΙΤΙΣΜΟ, ΤΗΝ ΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΗ, ΤΗΝ ΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑ". Η ΦΩΝΗ ΤΩΝ ΠΕΙΡΑΙΩΤΩΝ. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Γαΐλα, Τασσώ. "Πολιτιστικό Ίδρυμα Δαμαλά!". Tο μοσχάτο μου. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press.

- Kantakouzenos, John (c. 1356). Historiarum (Vol. 1 ed.). pp. 371, 379–80. ISBN 9781108043731.

- Angold, Michael (1984). The Byzantine Aristocracy, IX to XIII Centuries. British Archaeological Reports (Oxford) Ltd. ISBN 9780860542834.

- Hopf, Carl (1888). Les Giustiniani, dynastes de Chios: étude historique. Ernest Leroux.

- Battista de Burgo, Giovanni (1686). Viaggio di cinque anni in Asia, Africa, & Europa del Turco. Milan: Giuseppe Cossuto. ISBN 9789754282542.

- Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque: recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe (1205-1430). E. de Boccard.

- Missailidis, Anna (2012). THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY APOSTLES IN THE VILLAGE OF PYRGI ON CHIOS (Thesis). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.